Bitcoin Mixers and Tumblers

Bitcoin is a decentralized cryptocurrency that users can transfer on a peer-to-peer (P2P) network. Nodes on this network verify transactions through cryptographic means and record them in a public distributed ledger called a blockchain. The Bitcoin blockchain is completely public, meaning a blockchain explorer can show a complete record of all Bitcoin transactions ever processed since this cryptocurrency was launched in early 2009.

The public nature of Bitcoin isn’t a problem for many users, but it can be a huge flaw for those desiring greater anonymity when sending and receiving this cryptocurrency. Keeping Bitcoin transactions completely private requires the use of a Bitcoin mixer, or tumbler. These tools mix Bitcoin into private pools before sending them to their intended recipients, making transactions more difficult to trace.

The effectiveness of mixing services in obscuring financial transactions varies greatly, and not all of them are legitimate. It’s therefore crucial to thoroughly research mixers before using them. While not illegal in themselves, mixers are routinely used in money laundering to hide illegitimate sources of income.

Overview

Bitcoin mixing services like JoinMarket and Samourai combine multiple funds with potentially identifiable sources, which obscures the path back to the funds’ original sources. This process generally involves pooling funds for a random, but generally long period, before sending them to their intended destination. It’s very difficult to trace these transactions because the funds were mixed together and distributed at random intervals.

Assume, for this example, that person A sends 10 Bitcoin to person B. Shuffling this transaction through a black box makes it more difficult to identify this transaction because a public explorer will only show that person A sent some Bitcoin to a mixer, as did some other people. It will also show that person B received some Bitcoin from a mixer, along with some other people.

How Does a Crypto Mixer Work?

The algorithm for working with a mixer is not complicated and aims to leave the initial or final owner unknown. The mechanism is approximately the same among services but may differ depending on the functionality of a particular service. The general scheme of the mixer is as follows:

- A person buys cryptocurrency.

- Send coins to a crypto mixer.

- The coins are mixed. Here, the user can choose the degree/time of mixing and/or the amount of commission (all these factors are directly related to the quality of mixing).

- Later, the user receives a guarantee letter from the cryptomixer, which will help them contact technical support and sort out any problems in case of any problems. It is logical that the mixer does not store or require any data about the user.

- Then, the client of the service receives the same coins, but from among the mixed ones.

The most important thing is to choose the right crypto mixer so that you don't send your cryptocurrencies to scammers. Experts advise to start by trying to send a small amount to test the service, and if everything goes well, mix the required amount of coins.

Types of Mixers

Bitcoin mixers may generally be classified into centralized, decentralized and smart contract types.

Centralized Mixers

Centralized mixers send the equivalent cryptocurrency to the address specified by the user or the mixing service, less the service’s fee. There’s no definitive link between the cryptocurrency the user sends and that received by the recipient. However, the service is both centralized and custodial, so it records the data needed to make those connections. As a result, the mixing provider could provide records that establish a user’s connection to a particular Bitcoin.

Centralized mixers include Blender.io, which accepts Bitcoin from customers and returns other Bitcoin in exchange for a fee of one to three percent of the transaction value. They offer an easy solution to mixing, but they still pose a challenge to users wanting complete anonymity.

Decentralized Mixers

Decentralized mixers include JoinMarket and Wasabi. These mixers use protocols that completely obscure Bitcoin transactions via a coordinated or P2P approach. Either way, the protocol allows large numbers of users to join their Bitcoins together and redistribute them so that each person gets the same amount of Bitcoin that they put in, although no one knows who got which Bitcoin. Decentralized mixers are non-custodial, meaning they never actually hold the users’ funds.

Smart Contract Mixers

Smart contract mixers are similar to decentralized mixers in that they’re both non-custodial approaches to mixing. However, smart contract mixers don’t send and receive funds in a single transaction, like decentralized mixers. Instead, users receive a cryptographic note when they send funds to a mixer that shows they made the deposit. Users can then send that note to the mixer requesting a withdrawal of funds to a new address. Users can wait as long as they want to withdraw these funds by using services called relayers, which provide the cryptocurrency needed to pay the fees for the withdrawal. This approach allows users to withdraw funds to a new address that has no connection with other services.

Peer-to-peer Tumbler

A P2P mixer is a type of mixer where users directly interact with each other to mix their cryptocurrencies. This is unlike centralized mixers, in which the mixing process takes place with the help of a third-party service. Also, do not confuse them with decentralized mixers. There, the interaction is provided by an automated service, while here, everything depends on two people who mix coins manually. A popular mechanism used in P2P cryptocurrency tumblers is CoinJoin, where multiple users combine their transactions into a single transaction with multiple inputs and outputs. This confuses the transaction trail. Such mixers are chosen for their lower fees. They are caused by the absence of a centralized service that would receive interest.

Limitations

Mixers have some limitations when it comes to ensuring the anonymity of transactions. Assume, for example, that Party A sends 10 Bitcoin to Party B, less the tumbler’s fee. A law enforcement agency can learn the Bitcoin amount and address of Party A without much difficulty. It can then look for a party that received that amount within that timeframe. If Party B is the only entity that received a matching amount, then the flow of money can be reconnected. This problem becomes harder to solve as the number of parties using the mixer increases.

In addition, some exchanges don’t allow Bitcoin with mixed sources. Exchanges can identify mixers, so they may label mixed Bitcoin as tainted. For example, Binance is an exchange that blocks the withdrawal of Bitcoin to Wasabi, which is a Bitcoin wallet that integrates the CoinJoin mixing service.

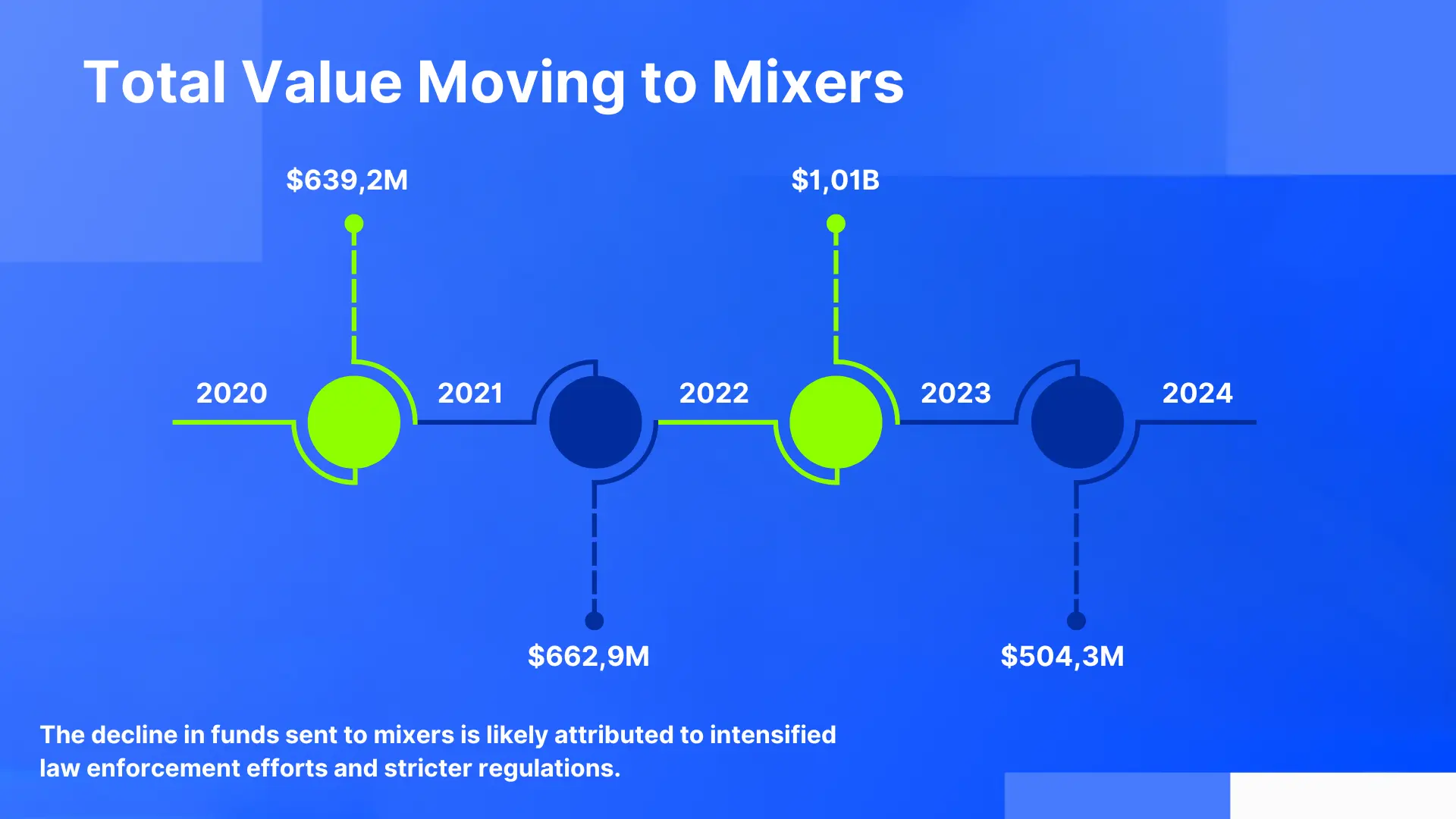

These limitations mean that mixers are likely to become obsolete in the near future as techniques for demixing transactions continue to develop, allowing authorities to identify the original source of funds. This is especially true for criminal enterprises, where the transactions can be quite large. As of 2022, however, mixers continue to receive more funds than ever.

Legality

There are many legitimate reasons for using mixers. For example, financial privacy is especially important to people living in countries with oppressive governments. However, the ability of Bitcoin mixers to obfuscate transactions makes them attractive to criminals who want to hide income. This typically includes money launderers, who want to disguise illegal sources of income, as well as those with legitimate income who simply don’t want to pay taxes on it.

In addition, mixers rarely ask for Know Your Customer (KYC) information, making it even more beneficial for cyber criminals. As a result, almost ten percent of funds sent from illicit addresses are sent to mixers, far more than any other service type. Despite their usefulness to criminals, mixers aren’t illegal by themselves in the United States. However, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) does consider them to be money transmitters as defined by the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), meaning they have an obligation to develop anti-money laundering (AML) programs and meet a host of reporting requirements. FinCEN also enforces these regulations, which can result in both criminal and civil penalties.

In addition, laws on mixers are changing rapidly, so crimes involving mixers have been successfully prosecuted since 2020. For example, Brian Benczkowski, U.S. Deputy Assistant Attorney General at the time, stated in February 2021 that using mixers to hide cryptocurrency transactions was a crime. In April of that year, Roman Sterlingov was arrested by U.S. authorities for his role in laundering money with Bitcoin Fog, a Bitcoin tumbling service he founded in 2011. BitCoin Fog laundered over $335 million during its ten years of operation. In addition, Larry Harmon, owner of the Bitcoin mixing service Helix, pled guilty in 2021 to helping criminals on the darknet launder about $300 million.

Financial regulators are currently passing additional measures to prevent mixing services from being used to launder money. For example, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) implemented its travel rule in 2012, which controls wire transfers. The European Union (EU) passed its Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD) V in 2020, which will also make Bitcoin tumblers a less viable option for money launderers. On the other hand, it will also make it more difficult for people to join the crypto economy by relying on popular exchanges.

Money Laundering

Bitcoin mixers are most often mentioned in the context of money laundering. Their ability to conceal the origin and ownership of funds is directly used by criminals to “cleanse” cryptocurrency obtained through illegal activities: hacker attacks, ransomware attacks, or illegal trading on dark web markets. Usually, they use decentralized mixers based on CoinJoin that are not controlled by any central organization.This makes it even more difficult to trace the funds.

What makes it even more difficult to investigate the hackers' activities is that after the “cleaning” the coins are transferred to newly created wallet addresses. These addresses will usually not be linked to the original wallet, which makes blockchain analysis much more difficult.

The most popular laundering services:

- Tornado Cash: The infamous mixer used by the North Korean hacker group Lazarus to launder more than $100 million in stolen funds since March 13, 2024.

- ChipMixer: Probably used by criminals to launder ransomware payments and illicit activity from darknet markets.

- Wasabi Wallet: Known for its CoinJoin implementation, which is abused by criminals despite the fact that it is focused on the privacy of legitimate users.

Final Words

Bitcoin mixers are a really controversial topic, but they are a necessary and integral tool in the cryptocurrency ecosystem. They combine both the necessary privacy for users in a highly centralized environment where the right to anonymity is restricted and, of course, money laundering, which is a criminal practice. A high-profile case such as the one involving Tornado Cash, which was used by the Lazarus Group, clearly outlines the scale of this problem.

However, these gaps are steadily being filled and exchanges are increasingly labeling mixed bitcoins as tainted. Ultimately, regulation is evolving and it will be a matter of a few years to determine whether mixers can remain a viable privacy solution or simply disappear under increased scrutiny.

FAQ

What is a bitcoin mixer for?

A bitcoin mixer is a tool for increasing the confidentiality of cryptocurrency transactions. It works by combining bitcoins from several users and redistributing them to new addresses. This breaks the connection between the sender and the recipient in the chain. This makes it difficult for anyone, including blockchain analysts, to trace the original source and destination of funds.

Centralized

Using a bitcoin mixer is generally safe. However, it all depends on the service. Centralised mixers require users to trust the provider to redistribute funds, and have not much transaction privacy as they record user activity. This is a threat to anonymous transactions. Decentralized mixers are generally more secure. However, the question of the mixer's reputation remains open.

Are crypto mixers illegal?

In most jurisdictions, cryptocurrency mixers are not illegal, but their use can cause legal problems. Using tumblers for illegal purposes, such as money laundering, tax evasion, or concealing stolen funds, is a crime.

What is the difference between a mixer and a tumbler?

The terms ‘mixer’ and ‘tumbler’ are often used interchangeably, but they refer to the same concept: tools that allow cryptocurrency transactions to be anonymized by mixing coins. ‘Mixer’ is a more technical term, and “tumbler” is its colloquial version.