Crypto Crime Report 2025-2026: Insights from 2,500+ Real Investigations

Intro

This report is based on the analysis of 2,500+ real crypto crime investigations conducted by AMLBot across 2025-2026, covering fraud, theft, hacks, and post-incident tracing cases across multiple blockchains and services. Rather than focusing on isolated incidents or public breach disclosures, the study examines how crypto attacks actually unfold in practice — from the initial attack vector to post-incident fund movement, freezing, and recovery attempts.

Key Findings — 2025 Crypto Crime Report

- 65% of crypto incidents investigated by AMLBot in 2025 were driven by Social Engineering, not technical exploits.

- 2,500+ real investigations analyzed across fraud, theft, hacks, and post-incident tracing.

- Investment Scams were the #1 attack vector by case volume (25% of all cases).

- Phishing ranked #2 (18%) and Device Compromise #3 (13%).

- $9M+ in stolen assets traced to impersonation attacks in the last 3 months of the study period.

- ~75% freeze success rate when stolen funds were still in attacker-controlled wallets at investigation start.

- CEX breaches dominated total financial losses despite representing a small fraction of case volume.

Scope and Methodology of the Analysis

The analysis maps 15 distinct fraud and theft categories, classified by dominant attack vector, and compares:

- case frequency versus financial impact, highlighting the divergence between how often incidents occur and where losses concentrate,

- high-volume retail-driven schemes versus low-frequency, institution-scale events, including rare but catastrophic CEX breaches,

- purely technical exploits versus access- and trust-driven compromise, showing how many incidents labeled as “technical” originate at the human or operational layer,

- and post-incident outcomes, focusing on how freezing, tracing, and counterparty coordination shape loss containment and recovery potential in real investigations.

The findings show that modern crypto crime has entered a sustained operational phase, where losses are driven less by isolated vulnerabilities and more by persistent exploitation of trust, access, and process gaps. In addition, recovery outcomes depend not on guarantees, but on timing, visibility, and the ability to act before stolen assets disperse beyond control.

To download the full report, fill out the form below 👇

It is important to note that dataset is built on real post-incident investigations. In most cases, individuals and businesses approached AMLBot after an incident had already occurred. These cases were investigated using Tracer, as the primary on-chain investigation tool, allowing analysts to reconstruct fund movement, identify laundering patterns, and understand how attacks evolved after the initial breach.

Report Preview

Report Preview: What 2,500+ Real Investigations Reveal About Crypto Losses in 2025

What Happens to Stolen Funds After an Attack

- ≈75% freeze success rate in cases where stolen funds were still held on attacker-controlled wallets at the time the investigation began

- freezing actions consistently precede recovery, serving as the primary mechanism for loss containment

- double-digit recovery rates observed in categories such as Device Compromise, Protocol Exploits, OTC Scams, and Impersonation, particularly when stolen assets intersect with centralized platforms or cooperative service providers

- recovery likelihood increases in high-value cases, where issuers, exchanges, and counterparties prioritize fast intervention, illustrating that timely investigative action and ecosystem cooperation remain critical factors in determining how stolen cryptocurrency can be recovered.

Сrypto Attack Vectors Observed in Real Investigations

This section outlines the primary attack vectors identified across AMLBot’s internal investigation cases. The initial point of compromise defines each vector. This approach reflects how incidents unfold operationally and aligns with the human-factor thesis that underpins this report. Where relevant, links to previously published AMLBot case studies are included to provide concrete, real-world illustrations of these mechanisms.

Investment Scams and Pig Butchering

Investment Scams represent the largest category by case count in AMLBot’s dataset. These schemes rely on false profitability signals (fabricated dashboards, staged withdrawals, or social proof) to gradually extract increasing deposits from victims.

A particularly damaging subset is Pig Butchering, where a prolonged trust-building phase precedes the financial scam. Victims are engaged through social platforms or messaging apps, often over weeks or months, before being introduced to a fraudulent investment opportunity. A detailed operational breakdown of such schemes is documented in AMLBot’s investigation into Pig-Butchering Crypto Scams.

Because losses accumulate slowly and appear legitimate during early stages, victims typically recognize the fraud late, reducing the likelihood of timely freezes or recovery. This behavioral pattern is further explored in AMLBot’s analysis of how emotional manipulation precedes financial loss.

Phishing, Impersonation, and Chat-Based Scams

Phishing remains one of the most common entry points across crypto-related incidents. However, in practice, many cases extend beyond simple malicious links or fake domains.

In a growing number of investigations, the defining vector is Impersonation. Attackers posing as exchanges, compliance teams, law enforcement, employers, or trusted counterparties. These scams rely on urgency, authority, and conversational pressure rather than technical deception alone.

Chat- and Voice-Based Impersonation (via Telegram, Discord, WhatsApp, Zoom, or Phone Calls) has become particularly prominent in 2025, reflecting a shift toward more interactive and psychologically tailored attacks.

While individual losses in these categories are often smaller than in Investment scams, their frequency and scalability make them a persistent operational risk for both individuals and businesses.

Device Compromise and Private-Key Exposure

Device Compromise cases consistently produce some of the highest median losses in AMLBot’s dataset. These incidents typically originate from phishing-delivered malware, fake software updates, compromised installers, or remote-access tools. Once installed, attackers gain access to wallets, signing sessions, password managers, or two-factor authentication mechanisms.

At that point, loss escalation is rapid. Unlike Investment scams, where funds are extracted over time, device compromise typically results in near-immediate draining of all accessible assets.

Address Poisoning and Operational Errors

Address Poisoning exploits a subtle yet critical operational weakness: reliance on transaction history to reuse addresses. Attackers generate addresses visually similar to legitimate counterparties and send small “dust” transactions to the victim. When the victim later copies an address from their transaction history, funds are inadvertently sent to the attacker-controlled wallet. While Address Poisoning accounts for a relatively small share of total cases, losses can be substantial, particularly in corporate or treasury contexts where a single transfer may involve six- or seven-figure sums.

Fake Job and Recruitment Scams

Job-related scams target victims through fake Web3 recruitment offers, freelance tasks, or “trial assignments.” Victims may be asked to install tools, sign transactions, provide credentials, or even unknowingly launder funds as part of supposed onboarding tasks.

These scams are particularly effective against early-career professionals and freelancers seeking entry into the crypto industry. Although median losses are typically lower than in investment scams, job scams frequently serve as initial access vectors that later escalate into device compromise or impersonation-based fraud.

CEX Breaches and High-Impact Incidents

Centralized Exchange breaches and protocol-level hacks are often perceived as purely technical incidents. However, AMLBot’s investigative data shows that many such cases involve human-enabled entry points, including credential theft, insider manipulation, or social engineering of employees. In the dataset, the “CEX Breach” category is influenced by a few mega-events, including a single outlier that dominates total loss figures. This underscores the importance of separating frequency analysis from impact analysis.

Data-Driven Analysis of Crypto Crime Patterns

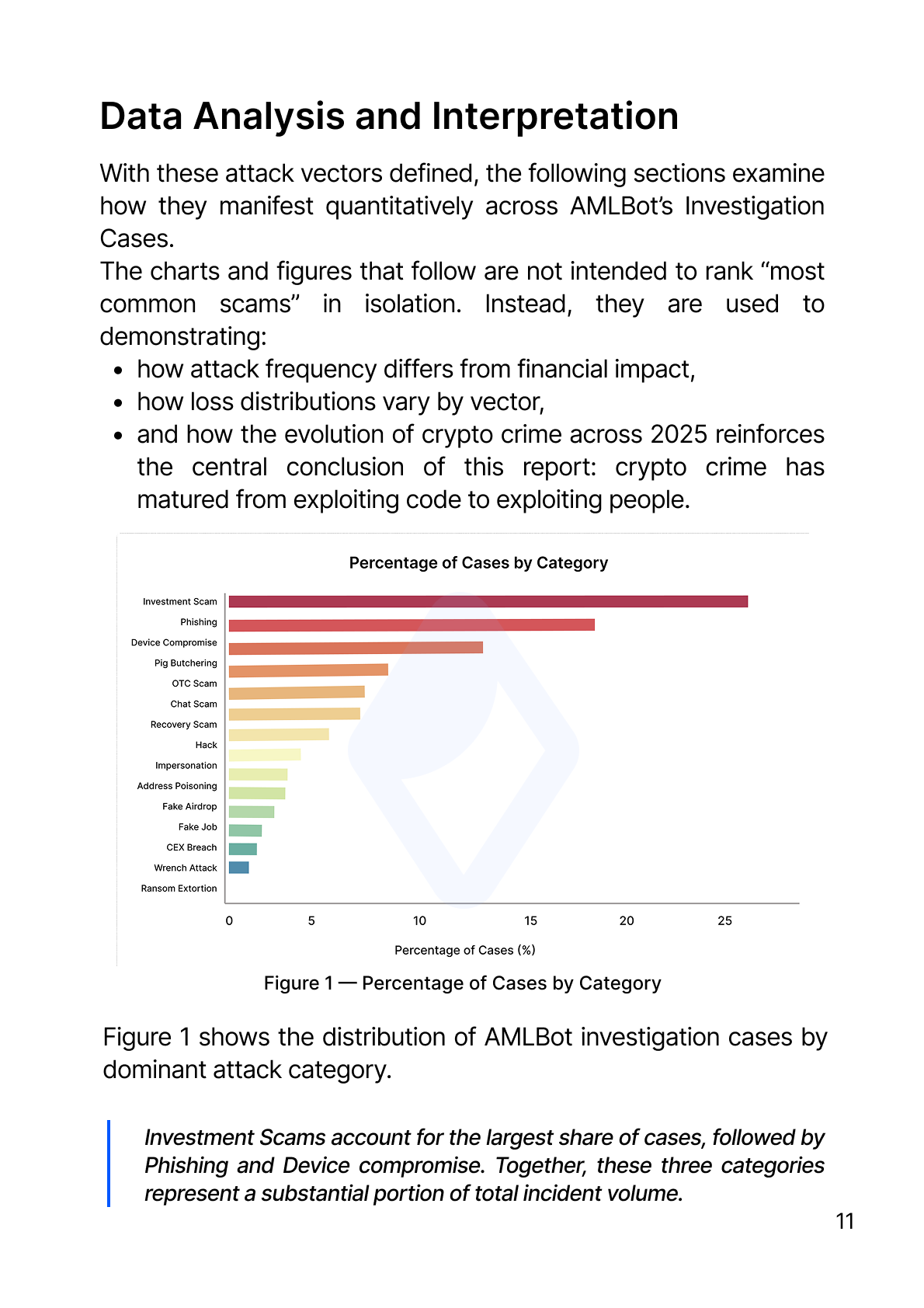

With these attack vectors defined, the following sections examine how they manifest quantitatively across AMLBot’s Investigation Cases. The charts and figures that follow are not intended to rank “most common scams” in isolation. Instead, they are used to demonstrating:

- how attack frequency differs from financial impact,

- how loss distributions vary by vector,

- and how the evolution of crypto crime across 2024–2025 reinforces the central conclusion of this report:

сrypto crime has matured from exploiting code to exploiting people.

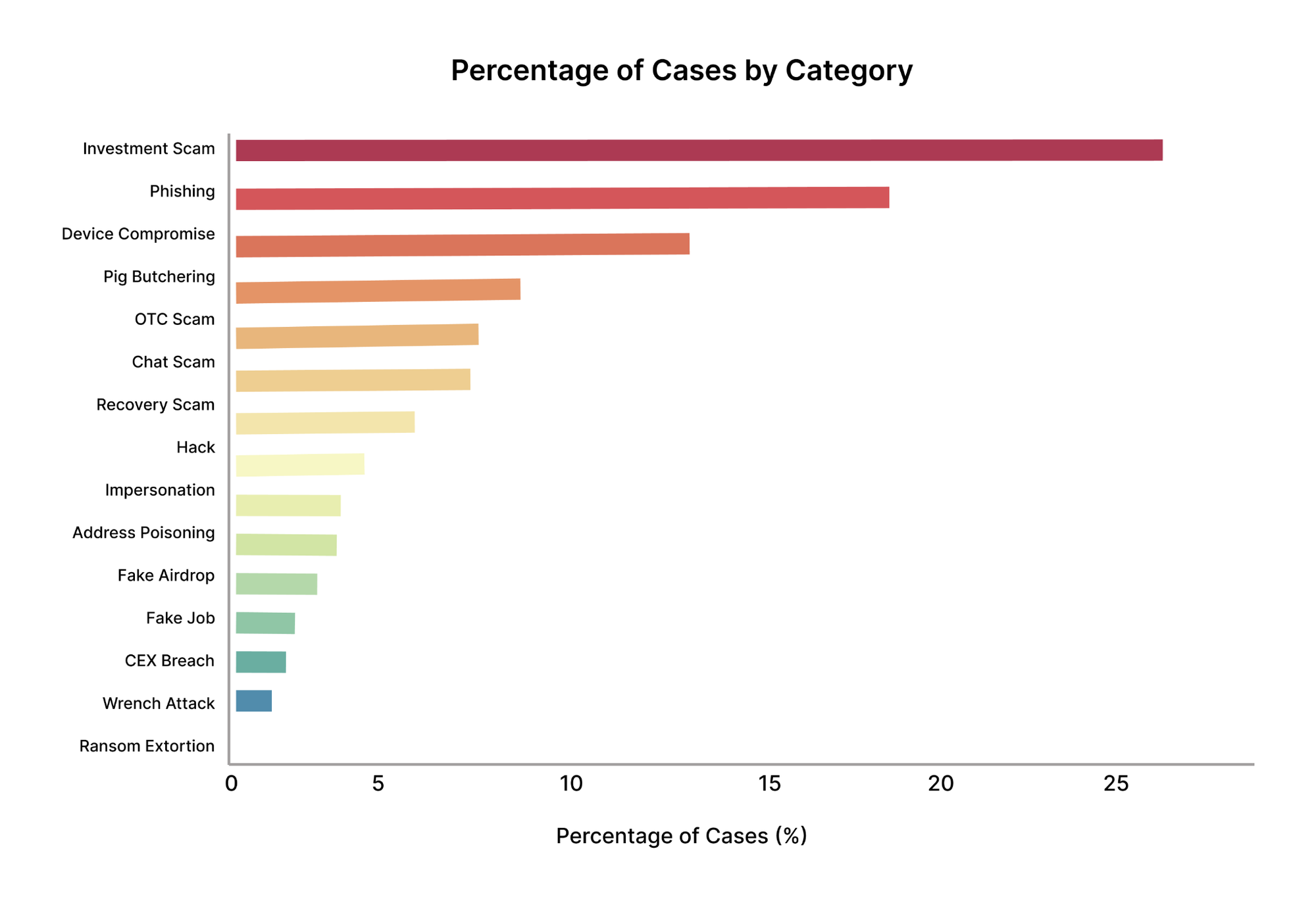

Figure 1 shows the distribution of AMLBot investigation cases by dominant attack category.

Investment Scams account for the largest share of cases, followed by Phishing and Device compromise. Together, these three categories represent a substantial portion of total incident volume. Pig-Butchering Scams, Chat-Based Impersonation, and OTC fraud form a second tier of frequently observed attack types. In contrast, categories such as CEX Breaches, Wrench Attacks, and Ransom/Extortion appear far less often.

Importantly, this distribution reflects case frequency, not financial severity. High visibility in this chart does not necessarily correspond to the largest financial impact, a distinction explored in subsequent figures.

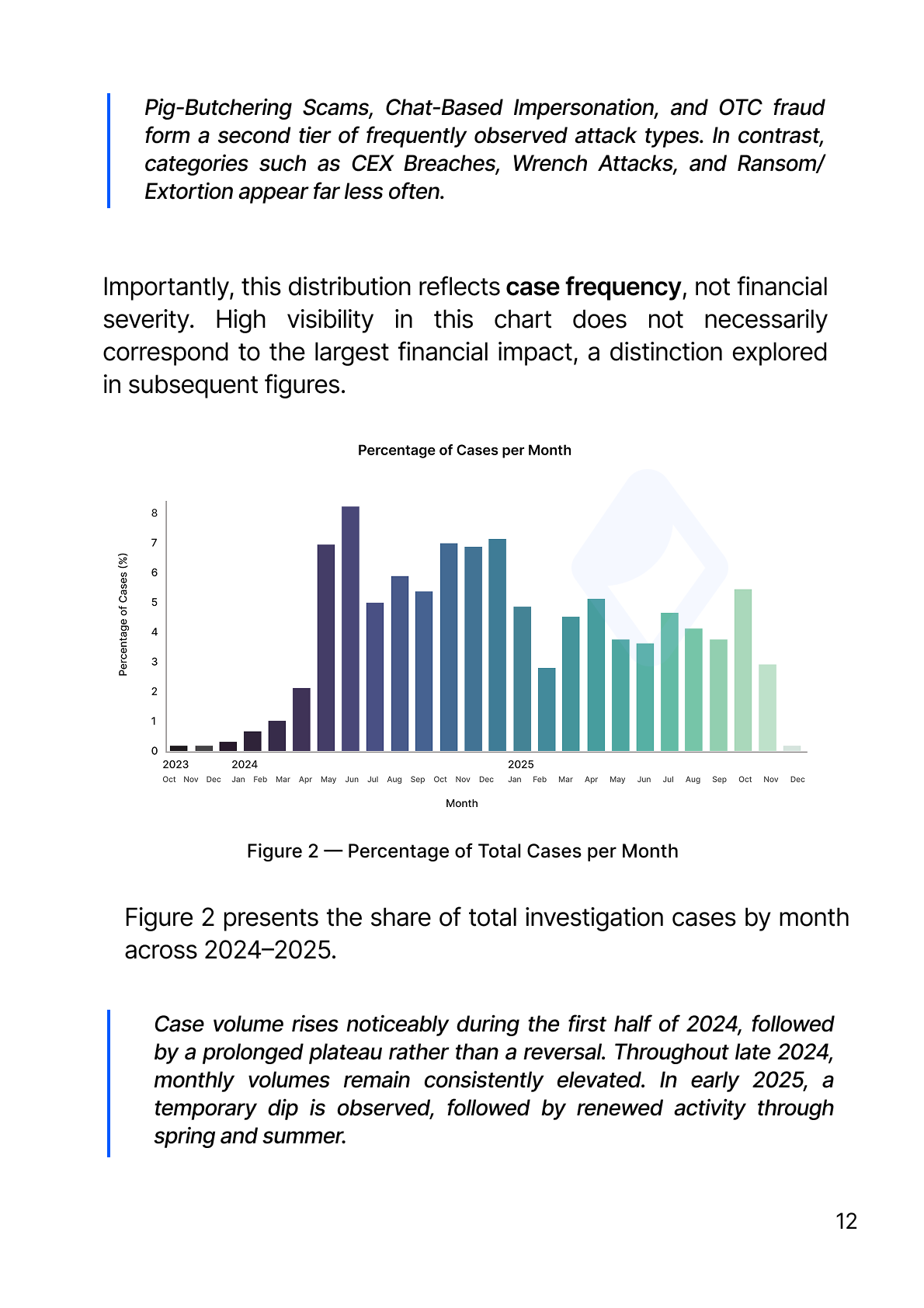

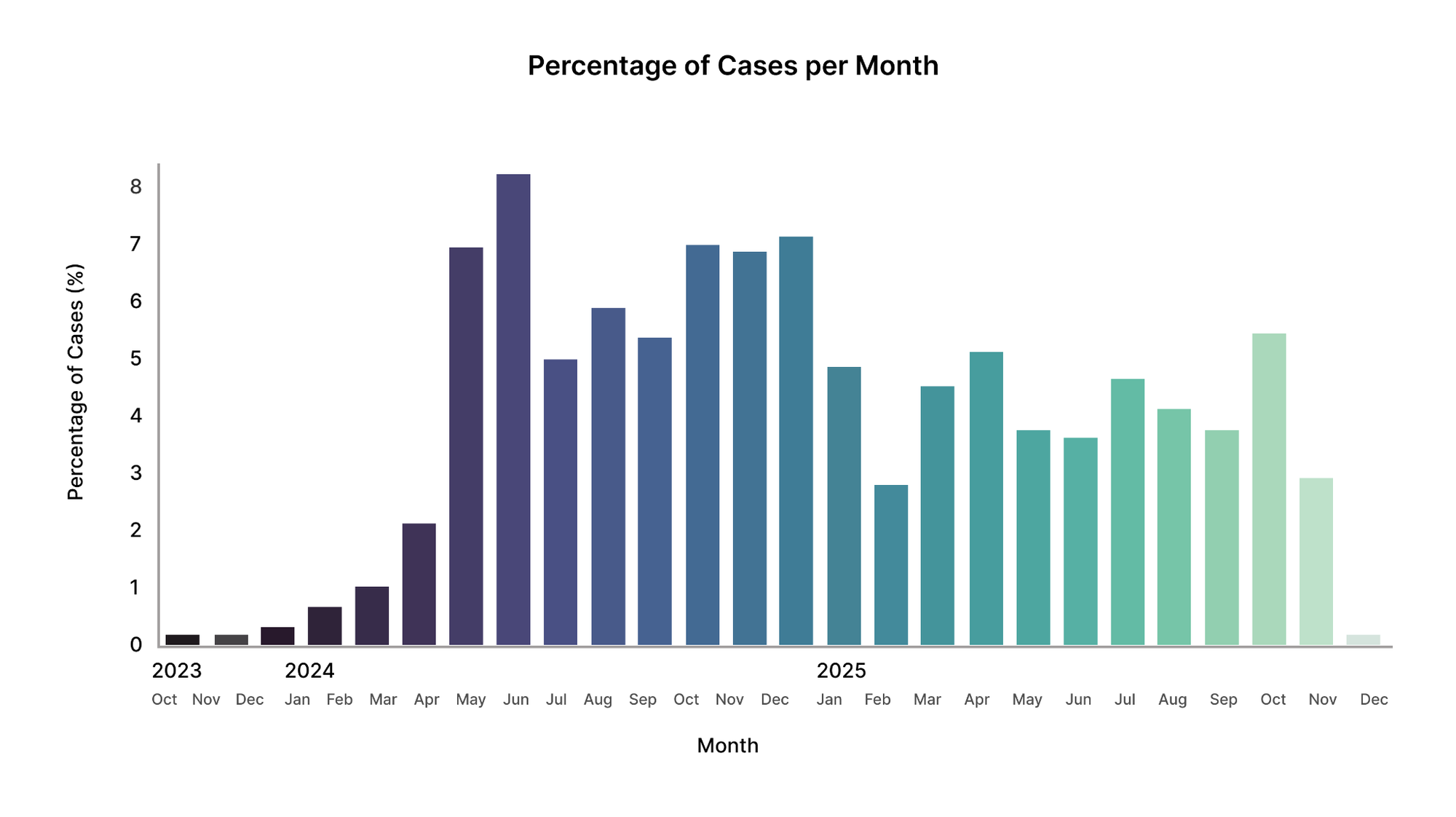

Figure 2 presents the share of total investigation cases by month across 2024–2025.

Case volume rises noticeably during the first half of 2024, followed by a prolonged plateau rather than a reversal. Throughout late 2024, monthly volumes remain consistently elevated. In early 2025, a temporary dip is observed, followed by renewed activity through spring and summer.

The data indicates a transition into a sustained operational phase of crypto-related fraud and theft, rather than a short-lived spike. The absence of a return to early-2023 baselines suggests structural persistence rather than event-driven volatility.

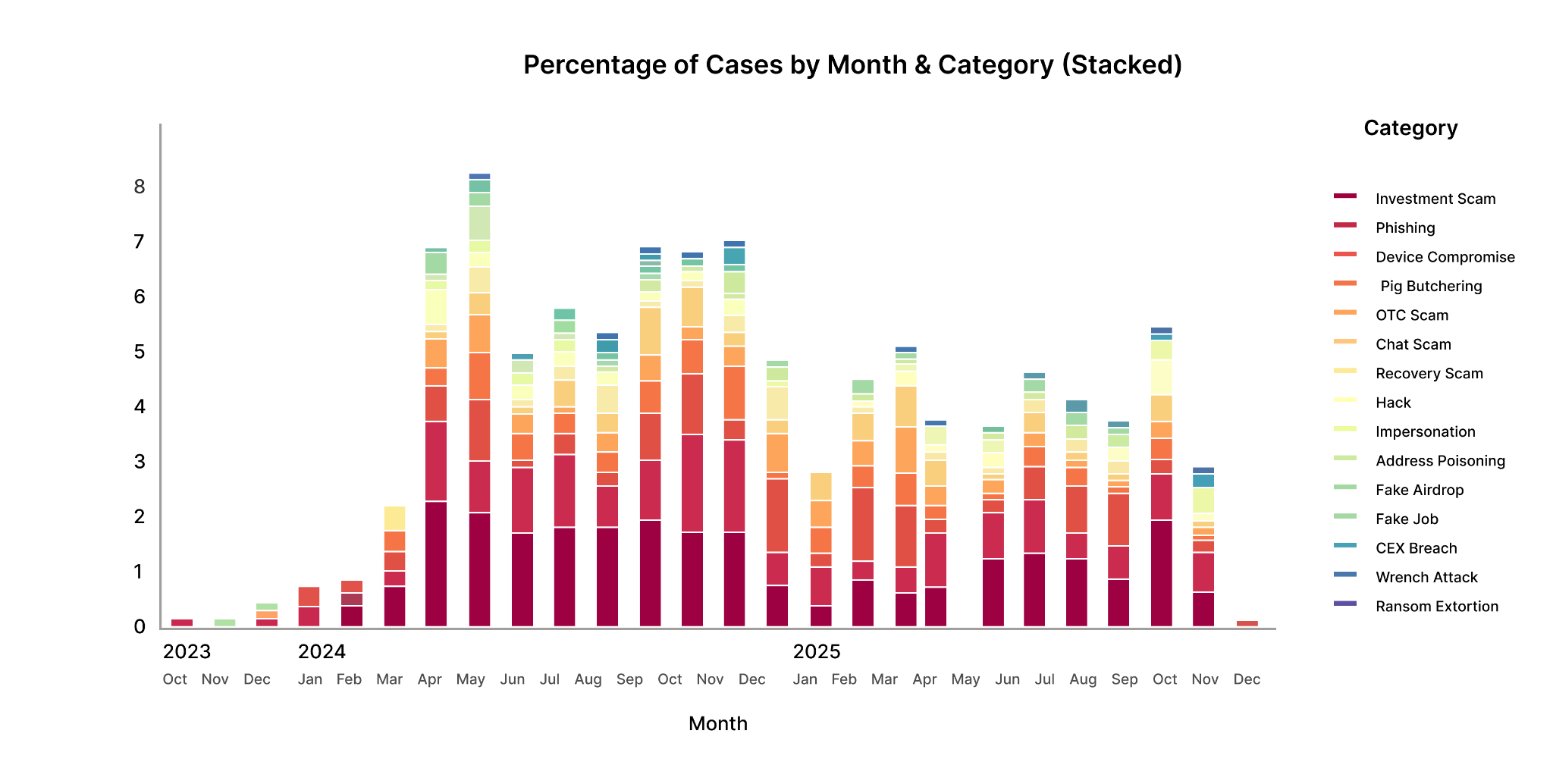

This stacked view breaks down monthly case volume by category, illustrating how different attack vectors contribute over time.

Early 2024 is dominated by Investment Scams and Phishing. As the year progresses, Device Compromise remains consistently present, while OTC Scams and Address Poisoning introduce steady background activity with occasional spikes. In 2025, chat-based and voice impersonation scenarios became more prominent within the overall mix.

A single dominant category does not drive the plateau observed in Figure 2, but by the simultaneous persistence of multiple attack vectors, each contributing moderate but sustained volumes.

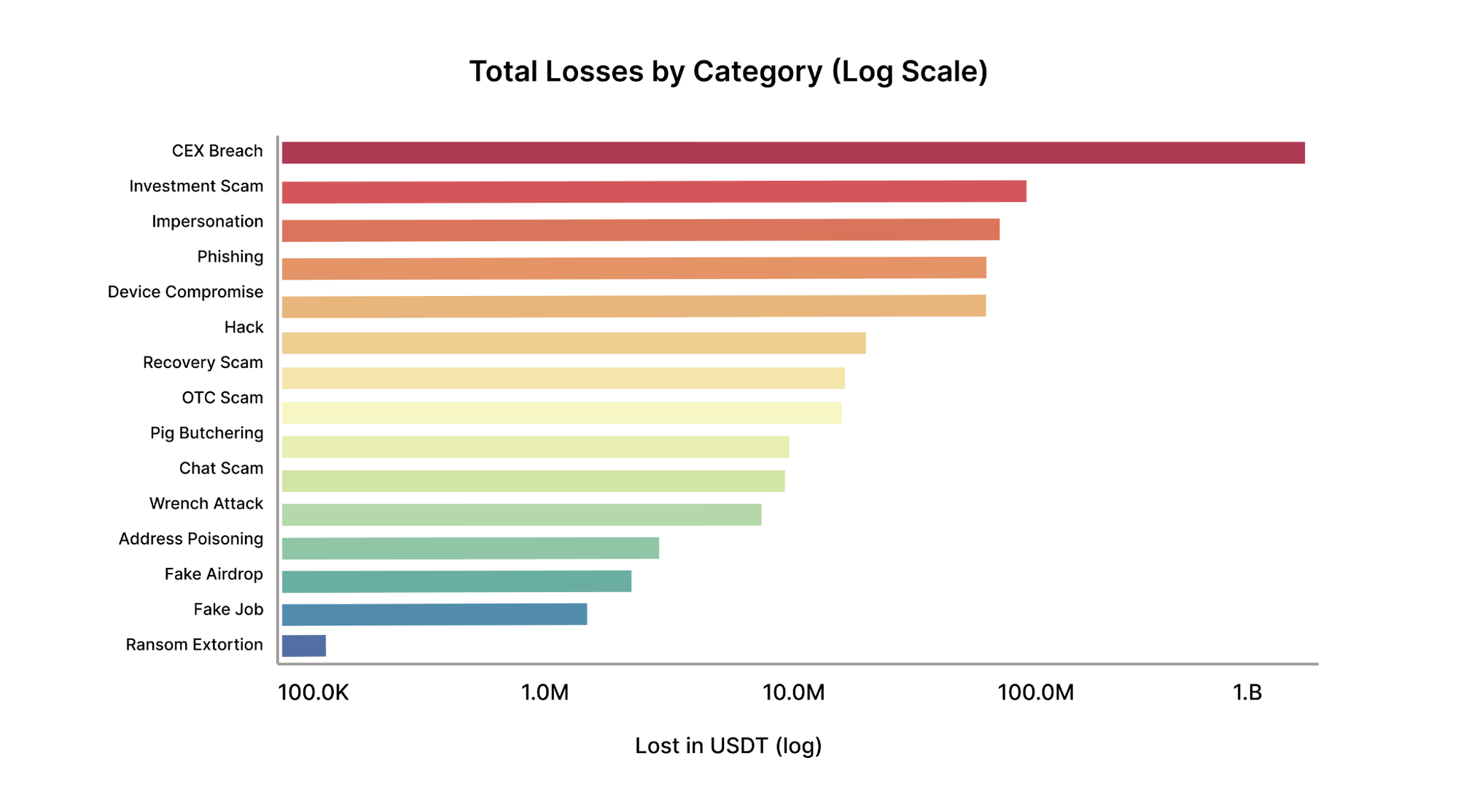

This figure compares total financial losses by category on a logarithmic scale. CEX Breaches dominate total losses, despite representing a small fraction of overall cases. This result is driven primarily by a small number of extreme outliers, including one mega-event that disproportionately skews aggregate totals. Investment Scams, Impersonation, Phishing, and Device Compromise also contribute significant cumulative losses.

Note: Aggregate loss figures are highly sensitive to rare, high-impact incidents. As a result, total losses should not be interpreted without reference to frequency and distribution metrics.

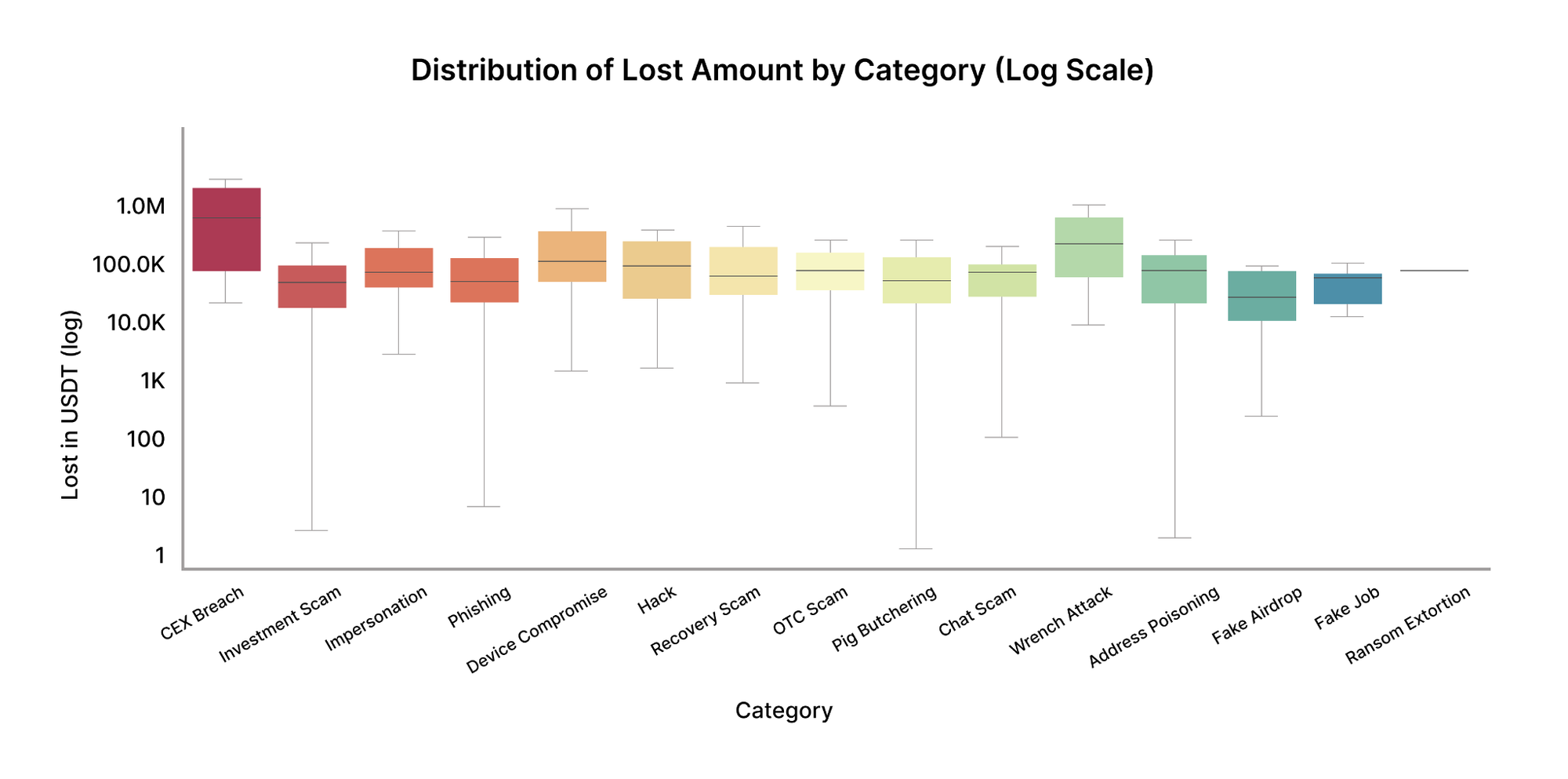

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of loss amounts per case across categories, highlighting medians, variability, and tail risk.

Device Compromise and Investment Scams show higher median losses and wide dispersion, indicating that once access is obtained or trust is established, losses can escalate fast. OTC Scams and Address Poisoning appear less frequently but exhibit notable outliers, particularly in operational or treasury-related contexts. Phishing, Chat Scams, Fake Jobs, and Fake Airdrops generally show lower median losses but remain highly recurrent.

Note: This figure differentiates typical loss exposure from tail risk. Categories with moderate frequency but broad distributions pose disproportionate risk to organizations with concentrated asset flows.

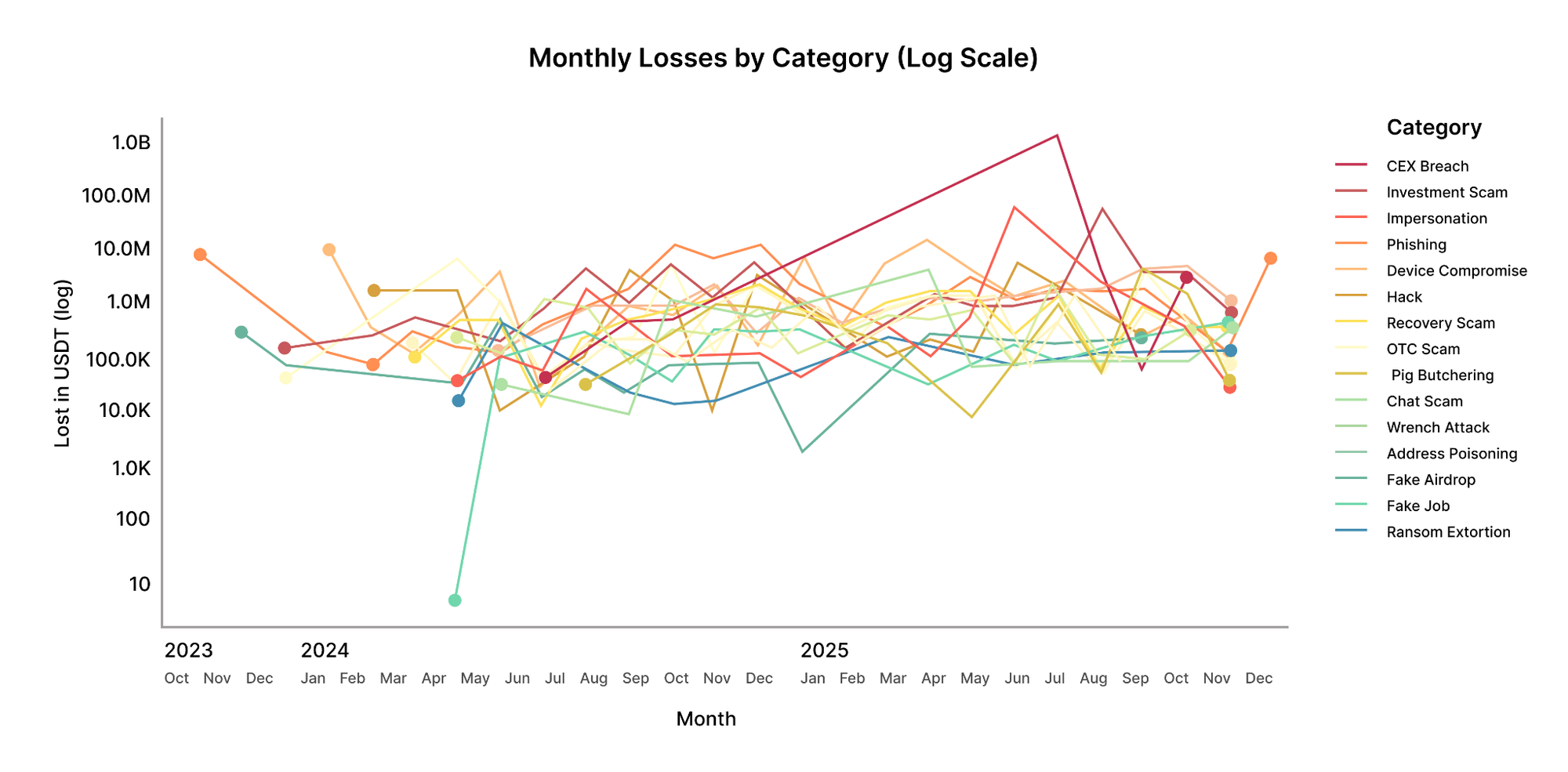

This time-series view presents monthly losses per category on a logarithmic scale. Loss patterns are characterized by high volatility, with extended periods of relatively moderate activity punctuated by sudden spikes. These spikes frequently correspond to isolated, high-value incidents rather than broad-based increases across categories.

Crypto loss dynamics are shaped less by gradual trends and more by episodic shocks. Risk assessments based on averages may therefore underestimate exposure to sudden, high-impact events. Taken together, the figures demonstrate a consistent pattern:

- High-frequency categories primarily exploit trust, urgency, and social pressure.

- High-impact categories often involve access compromise, operational errors, or insider-enabled pathways.

- Even incidents commonly labeled as “technical” frequently originate from human manipulation.

What Happens After the Attack

Once an incident is confirmed, the investigative focus shifts from detection to reconstruction and intervention. At this stage, outcomes are shaped less by how the attack occurred and more by how quickly fund movements can be identified, traced, and escalated.

Recovery Outcomes

Across categories, recovery outcomes correlate with time-to-detection. Early identification and freezing actions materially improve the likelihood of limiting losses, particularly in higher-value cases involving stablecoins or centralized intermediaries, forming the foundation for practical steps to recover stolen cryptocurrency.

By contrast, delayed recognition, common in Emotional Investment Scams and long-running Impersonation Schemes, reduces recovery potential, as funds are often fragmented across multiple wallets or routed through laundering paths before an investigation begins.

Freezing consistently emerges as the first and most decisive intervention step. In a significant share of cases, stolen funds were frozen before being moved further downstream. Larger thefts show even higher freeze rates, reflecting prioritization by exchanges and stablecoin issuers when high-value alerts are raised.

Importantly, when funds remained on attacker-controlled wallets at the time an investigation began, freezing actions were successful in approximately 75% of such cases, resulting in partial containment of losses. This figure does not imply full recovery, but it demonstrates that timely intervention can materially alter outcomes before laundering is completed.

Recovery, while less frequent than freezing, remains possible. Several categories, including Device Compromise, Protocol Exploits, OTC Scams, and Impersonation — show double-digit recovery rates, particularly when stolen assets touch centralized platforms or cooperative service providers.

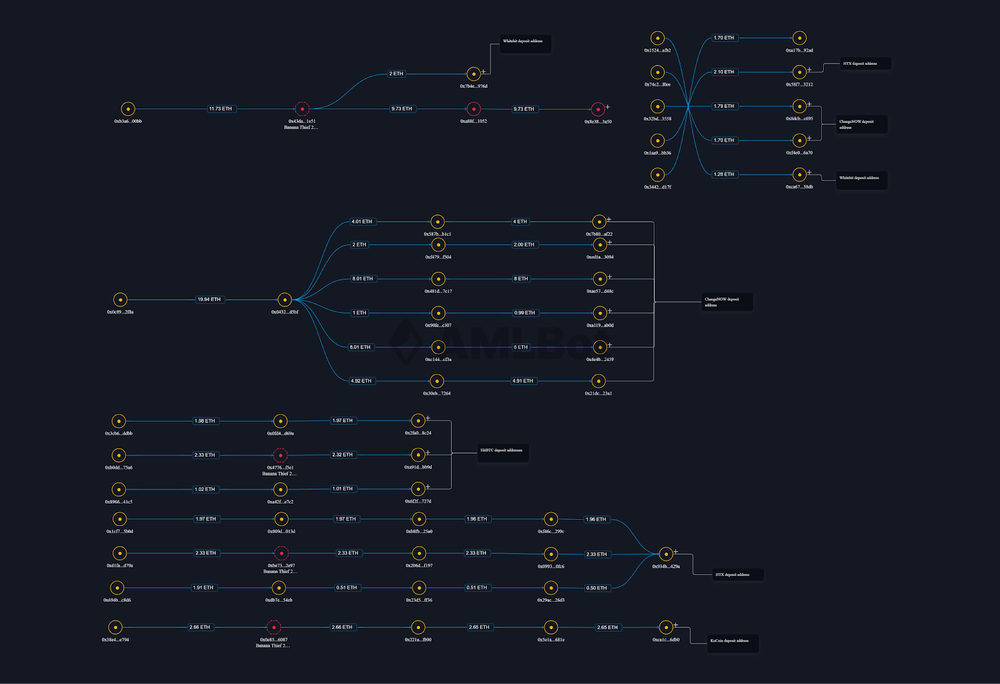

Post-Incident Investigation and Tracing

In AMLBot’s post-incident crypto investigations, AMLBot Tracer is used as the primary tool during this post-incident phase to reconstruct fund movements: mapping transaction paths, visualizing entity relationships, and identifying how attackers attempt to fragment, reroute, or extract stolen assets across chains and services. This post-incident window frequently determines whether losses can be contained or become irreversible. The ability to contextualize on-chain activity, attribute flows to known clusters, and escalate findings to counterparties directly influences whether freezing and recovery actions remain viable.

A practical illustration of this process can be seen in an Address Poisoning Сase investigated by AMLBot, where a victim lost approximately $50,000 after copying a spoofed address. Using Tracer, investigators were able to map the outbound transactions, identify consolidation points, and link the attacker’s wallet to known infrastructure. This attribution enabled timely coordination with counterparties, ultimately resulting in in a partial recovery of assets.

Final Summary and Strategic Takeaways

This analysis of AMLBot’s internal investigation cases from 2024 to 2025 highlights a shift in how crypto-related crime unfolds in practice. While technical exploits and protocol failures continue to attract the most public attention, they account for only a minority of investigation cases. The majority of incidents originate earlier in the attack chain — at the human, operational, and access-control layers.

The data demonstrates a clear divergence between incident frequency and financial impact. High-frequency categories such as Investment Scams and Phishing dominate case volume but do not always produce the largest losses per incident. Conversely, low-frequency categories, including Centralized Exchange Breaches, Access Compromise, and Operational Errors, generate disproportionate financial damage due to rare but extreme outlier events.

Importantly, incidents often labeled as “technical” rarely emerge in isolation. In many high-impact cases, technical exploitation is preceded by human manipulation, credential exposure, or procedural shortcuts. Blockchain infrastructure serves as the execution and settlement layer, but human behavior increasingly defines the true attack surface.

Across categories, recovery outcomes correlate strongly with timing. Early detection and freezing actions materially improve the likelihood of limiting losses, particularly in high-value cases involving stablecoins or centralized intermediaries. Delayed recognition, common in Emotional Investment Scams and long-term Impersonation scenarios, reduces the potential for recovery.

Taken together, the findings suggest that effective crypto risk management in 2026 cannot rely solely on code audits, protocol security, or on-chain monitoring. Organizations and individuals must address the operational reality of modern crypto crime: access management, transaction verification discipline, employee awareness, and incident response speed are now as critical as technical controls.

As crypto crime continues to professionalize, prevention and mitigation efforts must evolve accordingly — shifting focus from purely technical defenses to integrated human, operational, and investigative safeguards.

“Most of the serious crypto losses we investigate don’t start with broken code. They start with a human mistake that attackers know exactly how to exploit.” — Vasily Vidmanov, Chief Operating Officer, AMLBot