The Role of Customer Due Diligence in AML and KYC Compliance

Customer Due Diligence (CDD) is the cornerstone of modern Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC). In essence, CDD is the process by which banks, fintechs, and other businesses identify who their customers are, verify that information, assess the customer’s risk profile, and continuously monitor the relationship. By performing thorough CDD, institutions can detect and prevent illicit financial activity such as money laundering and terrorist financing.

This comprehensive guide explains what CDD is, why it’s required under AML regulations, the different levels of CDD (SDD, standard, EDD), key steps in the CDD process, and how a risk-based approach to CDD ensures effective compliance.

Note: None of this information should be considered as legal advice. While we’ve done our best to ensure this information is accurate at the time of publication, laws and practices may change, so please double-check it.

What Is Customer Due Diligence (CDD)?

Definition Of Customer Due Diligence

Customer Due Diligence (CDD) is a set of risk-based measures used by a business to:

- (a) Customer Identification: identify the customer by collecting core personal or legal entity information required to establish who the customer claims to be at the start of the relationship.

- (b) Customer Verification: verify the customer’s identity using reliable, independent sources to confirm that the information provided is accurate and belongs to the customer.

- (c) Beneficial Ownership Identification: identify and verify the beneficial owner where relevant, ensuring transparency over the natural persons who ultimately own or control the customer.

- (d) Purpose And Nature Of The Business Relationship: understand the intended purpose and expected activity of the relationship in order to establish a baseline for risk assessment and monitoring.

- (e) Ongoing Monitoring: maintain ongoing monitoring of the customer relationship and activity to ensure consistency with the customer profile and to detect unusual or suspicious behavior over time.

Customer Due Diligence is a regulatory-mandated process in which an organization verifies a customer’s identity, gathers information on the customer’s activities, identifies any beneficial owners, and evaluates the risk posed by that customer. In simpler terms, CDD means “Knowing who your Customer is” and understanding who really controls or benefits from the account (the beneficial owner). It also involves understanding the customer’s intended business purpose and monitoring their transactions for anomalies over time. CDD procedures are performed at the start of a business relationship and throughout the relationship as part of ongoing AML compliance

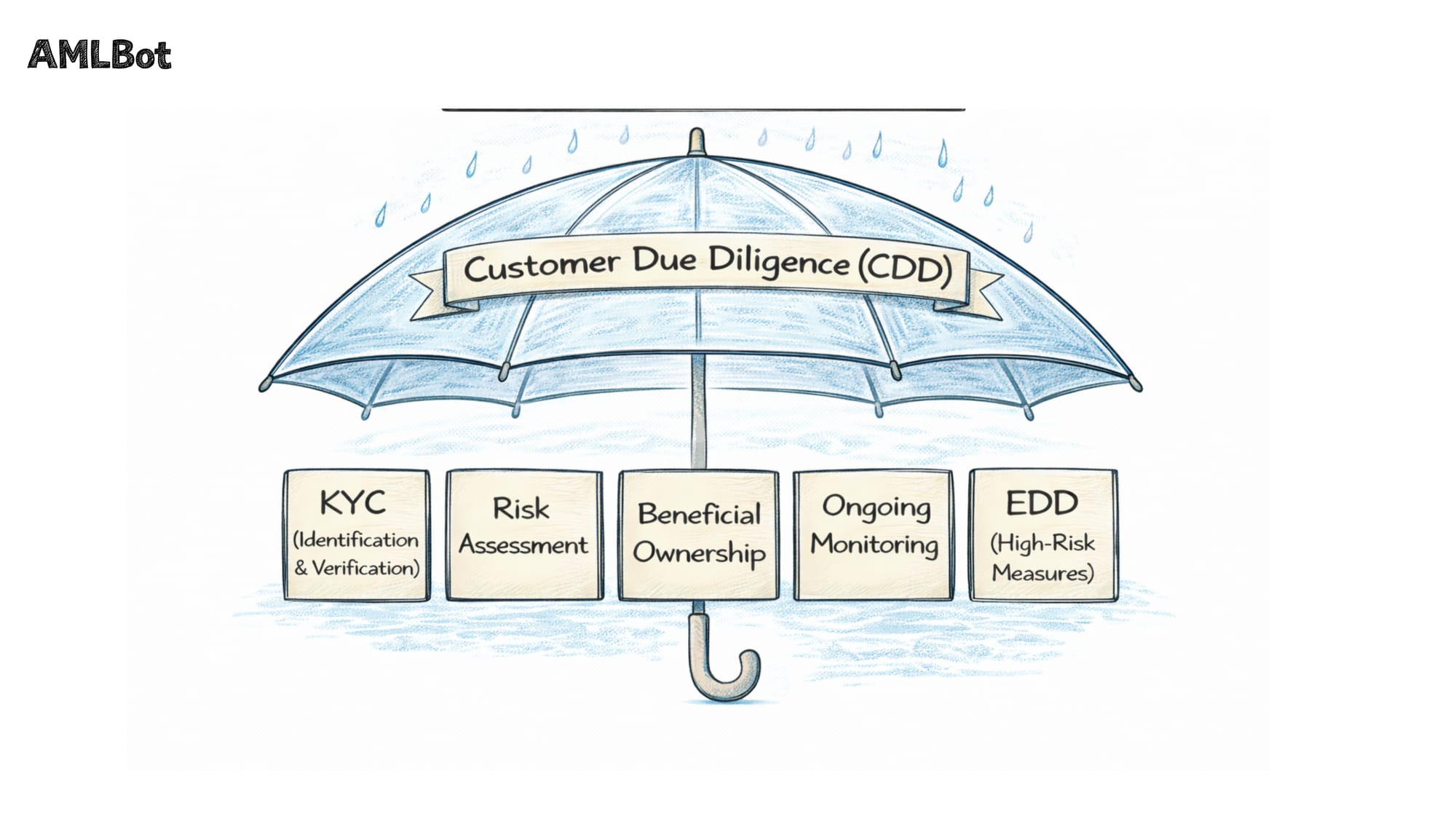

How CDD Fits Into AML And KYC Frameworks

CDD is the umbrella compliance process. The term Know Your Customer (KYC) refers to the set of requirements to identify and verify customers, which is essentially the first step of CDD. In other words, KYC is a critical component of Customer Due Diligence – you cannot perform CDD without first confirming your customer’s identity. However, CDD goes beyond basic KYC. While KYC focuses on customer identification and verification, CDD encompasses additional steps: assessing the customer’s risk profile, understanding the nature and purpose of the relationship, identifying beneficial ownership, and conducting ongoing monitoring of the customer’s transactions.

It’s also useful to note that regulatory guidance often uses the terms interchangeably or together. Many jurisdictions’ AML Compliance Obligations make KYC and CDD both mandatory steps.

Why Customer Due Diligence Is A Core AML Requirement

Preventing Money Laundering And Terrorist Financing

The primary purpose of CDD is to prevent criminals and terrorists from misusing financial services. By requiring institutions to verify identities and scrutinize customers, CDD makes it harder for bad actors to hide behind fake names or shell companies.

In practice, this means that CDD helps banks and businesses spot red flags early – for instance, an account that doesn’t match the customer’s expected profile or transactions that look suspicious. It enables the institution to report suspicious activities (filing SARs/STRs) and to avoid facilitating money laundering schemes.

Because of these high stakes, CDD is required under AML Regulations worldwide. Financial institutions have explicit AML compliance obligations to perform due diligence on customers in order to deter and detect money laundering and terrorist financing.

For example, U.S. regulations under the Bank Secrecy Act list ongoing Customer Due Diligence procedures as one of the “five pillars” of an effective AML program. In the EU and other jurisdictions, AML laws similarly mandate CDD as a fundamental requirement. Simply put, strong CDD is the frontline defense. t helps ensure that financial institutions know their customers and can keep illicit money out of the financial system.

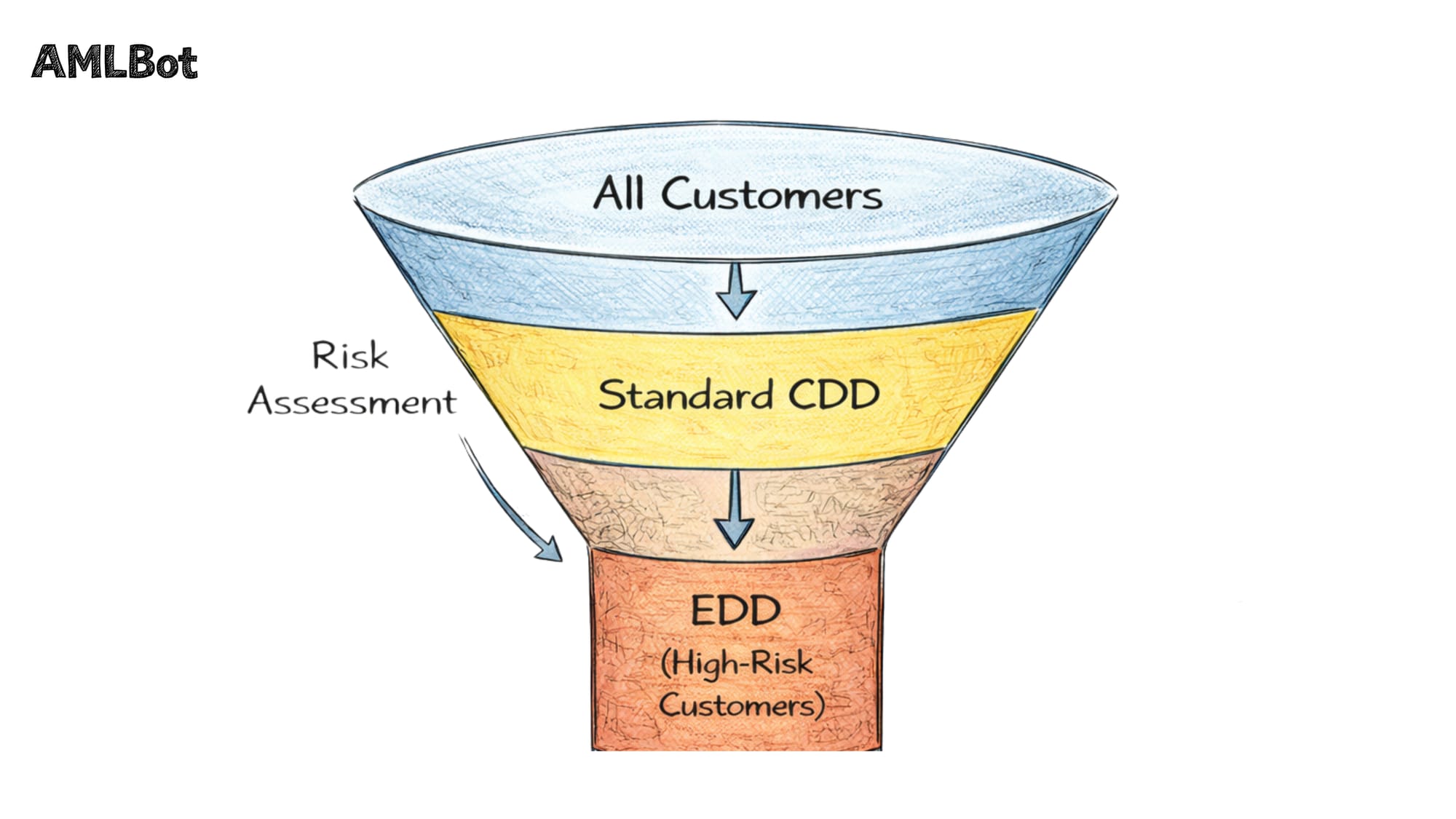

Risk-Based Approach To Customer Assessment

Modern AML regimes insist on a risk-based approach to CDD. Rather than applying identical checks to every customer, institutions are expected to tailor the extent of due diligence according to each customer’s risk profile. This approach is endorsed by regulators like FATF and the EU, as it allows compliance resources to be focused where they matter most. In practice, a risk-based approach means conducting more extensive checks for higher-risk customers and allowing simplified due diligence for low-risk customers (where a basic verification may suffice).

A well-implemented risk-based CDD program will include processes to categorize customers by risk level (e.g. low, medium, high) and then apply appropriate due diligence measures accordingly. High-risk scenarios – for example, a customer from a jurisdiction with weak AML controls or a business type prone to cash transactions – would trigger Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD) measures, such as collecting additional information and monitoring more frequently. On the other hand, customers deemed low-risk (say, a government entity or a publicly listed company with transparent ownership) might qualify for Simplified Due Diligence (SDD) with fewer checks. Regulators expect documentation of these risk assessments and rationales.

Regulatory Expectations And Enforcement

Global regulators have clear expectations that financial institutions will implement effective CDD programs, and they are increasingly enforcing these requirements. International standards such as the FATF Recommendations set the baseline. For example, FATF Recommendation 10 explicitly requires banks to perform CDD as part of a comprehensive AML program.

These standards have been incorporated into local laws and regulatory guidelines around the world. For instance, the European Union’s AML Directives and other national AML regulations closely mirror FATF’s Guidance, mandating customer identification, verification of beneficial ownership, a risk-based approach, and ongoing monitoring as part of CDD.

Failure to meet CDD requirements can lead to consequences. Regulators regularly penalize banks and businesses for inadequate due diligence – including fines, sanctions, or even license revocations for repeat or serious violations. In recent years, enforcement actions have reached record levels.

In 2023 alone, regulators worldwide issued approximately $6.6 billion in AML-related penalties, much of it tied to failures in CDD/KYC processes. These penalties underscore that weak CDD is not just a theoretical risk: it translates directly into compliance violations. Common regulatory findings include incomplete customer information, failure to verify beneficial owners, and lack of ongoing monitoring – all indicating lapses in due diligence. To avoid such outcomes, institutions must ensure their CDD process meets regulatory requirements and is well-documented. Regulators expect not only initial due diligence at onboarding, but also that firms maintain and update customer information (e.g. refreshed IDs, up-to-date beneficial owner data) and scrutinize transactions for suspicious activity on an ongoing basis.

Customer Due Diligence Vs KYC Vs EDD

What Is KYC?

Know Your Customer (KYC) refers to the steps a business takes to verify a customer’s identity and background. KYC is essentially the identification and verification component of due diligence – confirming that a person or business is who they claim to be. This typically involves collecting personal information (name, date of birth, address, identification number) and validating official documents (like passports, IDs, corporate registration documents). The goal of KYC is to establish a reasonable belief that the institution “knows” the true identity of each customer. KYC is performed at the onboarding stage of a customer relationship, before an account is fully opened or a service provided. It’s important to note that KYC is actually part of CDD. KYC processes create the foundation that feeds into the wider Customer Due Diligence process. Once a customer’s identity is verified via KYC, the institution can then assess the customer’s risk profile as part of CDD.

What Is Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD)?

Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD) is the term for additional, more in-depth measures of due diligence applied to high-risk customers or scenarios. While “standard” CDD is applied to most customers, EDD is required when a customer is identified as higher-risk – meaning there is greater potential they could be involved in money laundering, terrorist financing, or other illicit activity. Regulatory guidance triggers EDD in situations such as: the customer has numerous high-risk factors, the customer’s profile or activities are unusual, or the customer is involved in sectors/geographies with higher financial crime risk. For example, clients with complex corporate structures or opaque ownership, those from countries with weak AML controls, or cases where negative information arises would demand EDD.

Key Differences Between CDD, KYC, And EDD

| KYC | CDD | EDD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Verify the Customer’s Identity and basic information. | Assess customer risk by combining Identity Verification with broader business context. | Apply deeper scrutiny to high-risk customers through additional checks. |

| Scope of Checks | Identity Verification using official documents at onboarding. | KYC + Risk Profiling, Beneficial Ownership Identification, and Ongoing Monitoring. | All CDD measures plus enhanced verification and source of funds analysis. |

| When Applied | Applied to all new customers before access to services is granted. | Applied throughout the customer relationship, adjusted based on risk. | Applied only to high-risk customers or elevated risk scenarios. |

| Regulatory Requirement | Mandatory requirement under AML and KYC regulations. | Core AML compliance obligation requiring a risk-based approach. | Explicitly required by regulators for specific high-risk cases. |

| Data and Information Collected | Basic personal or business information and Proof of Identity. | KYC Data + Risk Profile, business activity, and Beneficial Ownership information. | In-depth ownership structures, Source of Funds, and Enhanced Background Data. |

As shown above, KYC and CDD are closely related. KYC is essentially a subset of the wider CDD process. CDD vs EDD is mostly a matter of degree: EDD is heightened due diligence applied when CDD indicates a higher risk level. All three concepts work together in an AML Program: KYC establishes identity, CDD evaluates risk and monitors, and EDD adds deeper checks for those few high-risk cases.

Levels Of Customer Due Diligence

In practice, customer due diligence is often described as having different levels or tiers. These levels align with the risk-based approach and ensure that institutions apply an appropriate degree of scrutiny based on risk. The three common levels of CDD are: Simplified Due Diligence (SDD), Standard (or normal) CDD, and Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD). Below, we explain each level and when it is applied.

Simplified Due Diligence (SDD)

Simplified Due Diligence is the lowest level of due diligence and is permitted only for customers who present a demonstrably low risk of Money Laundering or Terrorist Financing. When SDD applies, the institution can collect fewer details or perform reduced verification measures compared to standard CDD. This does not mean skipping CDD entirely, but rather doing the minimum required to still identify the customer and ensure there are no obvious red flags.

SDD is allowed in situations expressly defined by regulation or law as low-risk. For example, many regimes consider the following as potentially low-risk: customers that are government entities or public institutions, companies listed on a recognized stock exchange (which already disclose ownership), or products with a very limited scope like low-value accounts or certain insurance policies. In such cases, the risk of money laundering is inherently low, so regulators allow a lighter touch.

Standard Customer Due Diligence

Standard CDD (sometimes just referred to as “Customer Due Diligence” without qualifier) is the normal level of due diligence applied to the majority of customers. For most individual and business clients, institutions will perform this standard CDD, which includes all the core components of customer due diligence: collecting identifying information, verifying those details, checking for any sanctions or adverse media hits, determining the customer’s general risk category, identifying any beneficial owners (if the customer is a legal entity), and setting up appropriate ongoing monitoring. Standard CDD is essentially the baseline compliance process that financial institutions follow for every new customer unless an exception (SDD or need for EDD) is triggered.

For example, when a new retail banking customer opens an account, the bank will gather their personal data, verify identity documents, perhaps ask about the purpose of the account or source of initial deposit, and assign a preliminary risk rating. All that is part of the standard CDD process. The CDD requirements at this level are well-defined by regulations: verify customer identity, identify beneficial owners for legal entities, understand the purpose of the account, and monitor transactions.

Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD)

Enhanced Due Diligence is the highest level of scrutiny, reserved for those customers who pose a higher risk. As discussed earlier, EDD builds on the standard CDD measures by adding more thorough checks and analysis. When is EDD applied? Typically, when a customer is classified as “high-risk” during the initial risk assessment or when certain high-risk criteria are met. Common triggers for EDD include: the customer’s background or business is in an industry known for higher corruption or cash flows, the customer is from a country with poor AML controls, the customer is known to be a beneficial owner of multiple opaque companies, or the customer’s transaction patterns are highly unusual or large in volume. In some cases, simply the customer’s risk score being above a threshold will prompt EDD procedures.

Under EDD, an institution will seek more information and corroboration. For instance, the bank might require the customer to provide detailed documentation about the source of funds and source of wealth, especially if large sums are involved. They may perform on-site visits or interview the customer, seek independent verification of corporate documents, or consult external intelligence databases. If the customer is a legal entity, the institution might gather information on major shareholders, board members, etc., beyond what is normally required. Senior management approval is often needed before onboarding or continuing a relationship with a high-risk customer – this adds an extra checkpoint. Additionally, the account will likely be flagged for more frequent reviews and transaction monitoring (for example, reviewing the account quarterly instead of annually, or setting lower thresholds for automated alerts). EDD is critical because high-risk customers can pose serious legal and reputational risks to institutions if not properly vetted.

Key Elements Of The Customer Due Diligence Process

Customer Due Diligence is a multi-step process with several key elements that collectively provide a full picture of the customer. These elements are often outlined in regulations and guidance as essential components of CDD. The CDD process can be broken down into five primary steps: Customer Identification, Customer Verification, Beneficial Ownership Identification, Risk Assessment (Customer Profiling), and Ongoing Monitoring.

Customer Identification

Customer Identification is the first step of CDD, where the institution collects identifying information about the customer. For an individual, this typically includes the person’s full name, date of birth, address, and government-issued identification number. For a business or legal entity, identification involves obtaining details like the company’s official name, registration number, registered address, and the names of directors or account signatories.

Essentially, this step is about gathering the basic identity data that defines who the customer is.

Customer Verification

Once the customer’s identity information is collected, the next crucial element is Customer Verification. Verification means confirming that the identification information provided is accurate and genuine, and that the customer is not impersonating someone else. This is usually done by examining reliable, independent source documents or data. For individuals, this often involves verifying an official photo ID and possibly corroborating other information. For companies, verification may involve looking up the business in a corporate registry, obtaining a certificate of incorporation, or confirming the business’s existence and status through independent sources. In modern compliance programs, customer verification is increasingly aided by technology. Many institutions use an automated KYC verification process that can scan identity documents, perform biometric facial matching, and cross-reference databases to ensure IDs are valid and not reported lost or stolen.

Beneficial Ownership Identification

A critical element of CDD, especially for business customers, is identifying beneficial ownership. Beneficial owners are the natural persons who ultimately own or control the customer. In other words, if your customer is a legal entity (company, partnership, trust, etc.), you need to look past the company itself to see who really benefits from or controls it. Criminals often hide behind complex corporate structures to obscure their involvement, so regulators worldwide have made beneficial ownership transparency a key part of CDD. In practical terms, identifying beneficial ownership means that for a corporate account, the institution must determine if any individual owns (directly or indirectly) a significant percentage of the company (commonly a threshold like 25% ownership) or otherwise exerts control over the company’s management or policies. If such individuals exist, their identities must be collected and verified to the extent possible. If no individual meets the ownership threshold or control definition, the institution typically needs to identify a senior managing official of the company as the de facto beneficial owner for due diligence purposes.

For example, if XYZ Corp is owned 40% by Alice and 60% by ACME Inc (another company), and ACME Inc is in turn 100% owned by Bob, then the beneficial owners of XYZ Corp are Alice and Bob (assuming 25% threshold). The bank would gather Alice’s and Bob’s personal details and include them in the CDD file for XYZ Corp, verifying their identities similar to any customer.

Many jurisdictions have specific CDD Requirements around beneficial owners. The U.S. FinCEN CDD Rule (2018) requires banks to identify any beneficial owners (25% or more ownership or significant control) when opening accounts for legal entity customers. EU regulations likewise mandate that institutions “look through” corporate customers to capture beneficial owner information. The rationale is clear: to prevent the misuse of legal entities by ensuring the individuals behind them are known.

Risk Assessment And Customer Profiling

Armed with the information from Identification, Verification, and Beneficial Ownership checks, the institution then performs a Risk Assessment of the customer. This is where all the data is analyzed to assign a risk rating or profile to the customer.

- Customer Type: Is the client an individual, a private company, a bank, a charity, etc.?

- Geographical Risk: Where is the customer located or doing business? Are they from a country with high levels of corruption or weak AML controls? Are they operating in offshore financial centers?

- Product/Service Risk: What kind of account or service are they using? (A simple savings account vs. complex trade finance products, for example – some products have higher money laundering risk).

- Transaction or Activity Profile: What is the expected activity level (volume, value, types of transactions)? Does the customer deal in cash regularly?

- Industry/Sector: Is the customer’s business in a high-risk industry (e.g., gambling, crypto exchange) or a lower-risk one (e.g., retail groceries)?

- Reputation and Other Factors: Any adverse media about the person/business? Are they known to be close associates of high-risk persons?

Based on such factors, the institution will assess the overall risk – often categorizing customers into risk bands like Low, Medium, or High. This process is the embodiment of the risk-based approach in CDD.

Ongoing Monitoring And Review

Customer Due Diligence does not end after the initial onboarding. A foundational principle in AML compliance is that CDD is an ongoing obligation. Ongoing Monitoring means continuously observing customer activity and maintaining up-to-date customer information in order to spot any signs of suspicious behavior or changes in risk profile over time.

There are two main components to ongoing CDD:

- Transaction Monitoring: The institution monitors the customer’s transactions and account usage against expected patterns. If transactions occur that are inconsistent with what is known about the customer – e.g., sudden large wire transfers from a high-risk country, or a dormant account that becomes very active – these anomalies are flagged for further investigation.

- Periodic Reviews / Information Updates: At risk-based intervals, the institution should refresh the CDD information on file. For higher-risk customers, reviews might be annual. For lower-risk, perhaps every few years. During a review, the bank will ask if the customer’s information is still current and whether their business or activities have changed. If the customer has new lines of business or higher volumes, that may affect their risk rating. Maintaining updated customer data (including beneficial ownership information) is required by regulators as part of Ongoing Due Diligence.

The purpose of ongoing CDD is to ensure that the institution’s knowledge of the customer remains current and accurate, and that any suspicious changes are detected promptly. Financial crime risks can evolve, and a customer that started as low risk could become higher risk due to changes in behavior. Without ongoing monitoring, an institution would be blind to these developments. That’s why regulators emphasize that CDD is not a “one-off” event but a continual process. In fact, one of the FATF’s core CDD principles is that firms must conduct ongoing due diligence on the business relationship and scrutinize transactions throughout.

In summary, ongoing monitoring and review is the feedback loop of CDD – it keeps the due diligence dynamic.

Regulatory Expectations And Global Standards

FATF Recommendations

At the global level, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) sets the gold standard for AML and CDD requirements. The FATF is an inter-governmental body that issues the FATF Recommendations, which are internationally endorsed guidelines to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. These recommendations heavily influence national laws and regulations. FATF Recommendation 10 specifically covers Customer Due Diligence and outlines what is expected: financial institutions should identify and verify customers, identify beneficial owners, understand the purpose/nature of the relationship, and conduct ongoing monitoring as part of a risk-based approach. FATF standards also state when CDD must occur (e.g., at account opening, above certain transaction thresholds, when suspicious circumstances arise).

In addition to Rec. 10, other FATF recommendations touch on CDD-related issues: Rec. 22 and 23 extend CDD obligations to non-financial sectors, and Recs. 24 and 25 emphasize transparency of beneficial ownership for legal persons and arrangements. The FATF Recommendations are not laws themselves, but almost all countries have adopted them into their own legal frameworks. Therefore, FATF’s CDD expectations are effectively global expectations. Countries and institutions that fail to implement these standards can face FATF review and potentially be labeled high-risk jurisdictions (the FATF “grey list” or “blacklist”), which has reputational and economic consequences.

EU AML Directives And Global Approaches

Beyond FATF, various regions have their own frameworks that reinforce CDD obligations. In the European Union, the series of EU Anti-Money Laundering Directives (AMLD) have been instrumental in standardizing CDD across member states.

These directives – from the 4th AMLD through the recent 6th AMLD – all contain provisions on when and how to conduct customer due diligence. For example, the EU directives require a Risk-Based Approach to CDD, mandate identification of beneficial owners for all corporate customers, and specify scenarios requiring Enhanced Due Diligence. EU law also introduced the concept of Simplified Due Diligence for low-risk cases, albeit with clear limits on when SDD can be applied. By transposing FATF standards into EU regulations, the directives ensure that terms like “appropriate CDD measures” and “ongoing monitoring” are enforceable legal duties for banks, payment providers, casinos, and other obliged entities in Europe.

Globally, many countries outside the EU have similar laws often modeled after FATF and sometimes influenced by EU/US approaches. For instance, United States regulations (like the Bank Secrecy Act and FinCEN Rules) explicitly detail CDD requirements, including the 2018 CDD Final Rule focusing on beneficial ownership identification for legal entity customers. The U.K., even post-Brexit, retained an AML regime closely aligned with EU directives. Other jurisdictions in Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas follow suit: almost all require customer identification, verification, risk assessment, and ongoing monitoring as fundamental AML compliance requirements.

Customer Due Diligence Across Industries

Core CDD principles apply across all industries that have AML obligations, but how CDD is implemented can vary by industry. Financial institutions pioneered CDD practices, but now many sectors — from fintech startups to crypto exchanges — must also comply with due diligence requirements. Below we highlight CDD considerations in a few key industries: Banking/Financial, Fintech/Payments, and Crypto Businesses.

Banking And Financial Institutions

Traditional financial institutions are subject to the most extensive CDD regulations and also usually have the most mature CDD programs. In banking, Customer Due Diligence has long been a regulatory cornerstone, given banks’ central role in the financial system. Banks must perform CDD on a wide range of customers: retail account holders, corporate clients, trusts, correspondent banks, and so on. This means banks often have tiered CDD procedures to handle everything from a simple savings account for an individual to a complex account for a multinational corporation.

The volume of customers in banking can be enormous, so scalability is crucial – hence the push towards digital KYC solutions, centralized CDD utilities, and other technologies to streamline due diligence. Still, one of the biggest challenges banks face is balancing thorough CDD with customer service, as overly onerous checks can frustrate customers.

But there’s little choice: banks have to comply with strict CDD requirements to avoid penalties and protect the integrity of the financial system. Indeed, many of the largest AML enforcement fines have been against banks that failed to implement proper Due Diligence and Monitoring.

Fintech And Payment Service Providers

Fintech companies and payment service providers have risen as key players in financial services, and they too must adhere to AML/CFT and CDD standards. Fintechs can include digital banks, online payment processors, remittance platforms, lending platforms, e-wallet providers, etc. While the products and onboarding methods may differ from traditional banks (often entirely online and fast), regulators expect the same fundamental CDD controls to be in place. Many fintechs partner with specialized KYC/AML vendors or use Software-as-a-Service solutions to manage CDD compliance.

As the industry matures, the gap between fintech and bank CDD standards is narrowing. Fintechs, to earn trust and regulatory approval, often aim to match the robustness of bank compliance programs, while maintaining the seamless digital experience their customers expect. The mantra here is “compliance by design” – building CDD into the platform workflow so that it happens automatically and transparently.

Crypto Businesses (High-Level Overview Only)

The cryptocurrency and virtual assets sector is a newer industry facing AML requirements, and crypto businesses (such as cryptocurrency exchanges, trading platforms, wallet providers, and other VASPs – Virtual Asset Service Providers) are now subject to CDD obligations in most jurisdictions. While historically crypto operated in a gray area, today regulators worldwide have made it clear that crypto businesses must implement KYC and CDD similar to traditional financial institutions.

Crypto Customer Due Diligence entails many of the same steps: verifying customer identities, assessing risk, monitoring transactions for illicit activity (like detecting funds coming from hacks or sanctions-listed wallets). However, there are unique challenges: crypto transactions are pseudonymous by nature and global in reach. Thus, exchanges and platforms have to link blockchain addresses to real customer identities (via KYC) and use blockchain analytics (often termed KYT – Know Your Transaction) to trace sources of funds. Even though the question of blockchain monitoring (KYT) is beyond our scope here, it complements CDD by adding ongoing monitoring specific to crypto flows.

Crypto businesses must keep up with evolving crypto KYC regulatory requirements, which are becoming more aligned with traditional finance. For instance, by 2026 many jurisdictions demand that crypto exchanges perform customer due diligence and report suspicious transactions on par with banks.

One difference is that crypto platforms often deal with a tech-savvy user base that values privacy. Implementing CDD in this context requires careful communication to users about why it’s needed and how their information is protected. Many crypto companies have faced user resistance when introducing KYC, but regulators have made it clear that the era of anonymous crypto services is ending.

Common CDD Challenges And Compliance Risks

Even with clear procedures, implementing Customer Due Diligence is not without difficulties. Many organizations encounter common challenges and pitfalls in their CDD programs, which can turn into compliance risks if not addressed. Below are a few major challenges:

Incomplete Or Inaccurate Customer Data

One frequent issue is incomplete, false, or outdated customer data. If the information collected during CDD is wrong or not kept current, the whole due diligence process suffers. Criminals may provide fake identities or forged documents to evade detection. For example, someone might open an account with a counterfeit passport or using a “mule” (a third party’s identity). If an institution’s verification process fails to catch that, they essentially have a phantom customer in their system, defeating the purpose of KYC. Likewise, complex customers like shell companies may deliberately omit or obscure their beneficial owners, leading to beneficial ownership opacity. Without knowing who the true owners are, the institution can’t properly assess risk.

Additionally, customer circumstances change – addresses, phone numbers, even ownership structures – and if these aren’t updated via ongoing CDD, records become stale. Incomplete or inaccurate data creates blind spots. A risk is that when examiners or auditors come, they will find CDD files that are missing key documents or contain obvious inaccuracies, which is a compliance red flag. To combat this, organizations need robust identity verification and data management practices. Regular ongoing monitoring and periodic refresh of information are designed to tackle this challenge by ensuring that customer profiles remain accurate over time

Weak Risk Scoring Models

Another challenge is the use of weak or inadequate risk scoring models for customer assessment. Since the risk-based approach is central to CDD, a flawed risk assessment process can undermine everything. Some institutions rely on very simplistic risk rating questionnaires or outdated criteria that don’t truly differentiate higher-risk customers from low-risk ones. For instance, if a bank’s model places 90% of customers in “medium risk” by default without granular analysis, it might fail to flag those who really require Enhanced Due Diligence. Conversely, a bad model might over-classify customers as high-risk, creating unnecessary workload and noise.

Weak risk models could stem from not incorporating enough data (e.g., ignoring adverse media or external risk indicators), not updating the risk factors in light of new threats, or lack of calibration/testing of the model’s output. The result is inconsistent or inaccurate risk profiles. This poses compliance risk because regulators expect to see that high-risk customers in reality were treated as high-risk (with EDD applied). If an investigation later finds that a client involved in money laundering was inaccurately tagged as low risk by a bank’s system, it points to a deficiency in the bank’s CDD program.

Organizations must regularly review and improve their risk assessment methodologies. This can include integrating new risk factors, using advanced analytics or machine learning to find hidden patterns, and aligning the model with regulatory expectations (for example, making sure the model accounts for factors regulators consider important, like involvement in certain high-risk industries or use of cash). Without a robust approach, the risk-based customer due diligence process fails its purpose – resources won’t be properly focused, and suspicious customers might slip through with insufficient scrutiny.

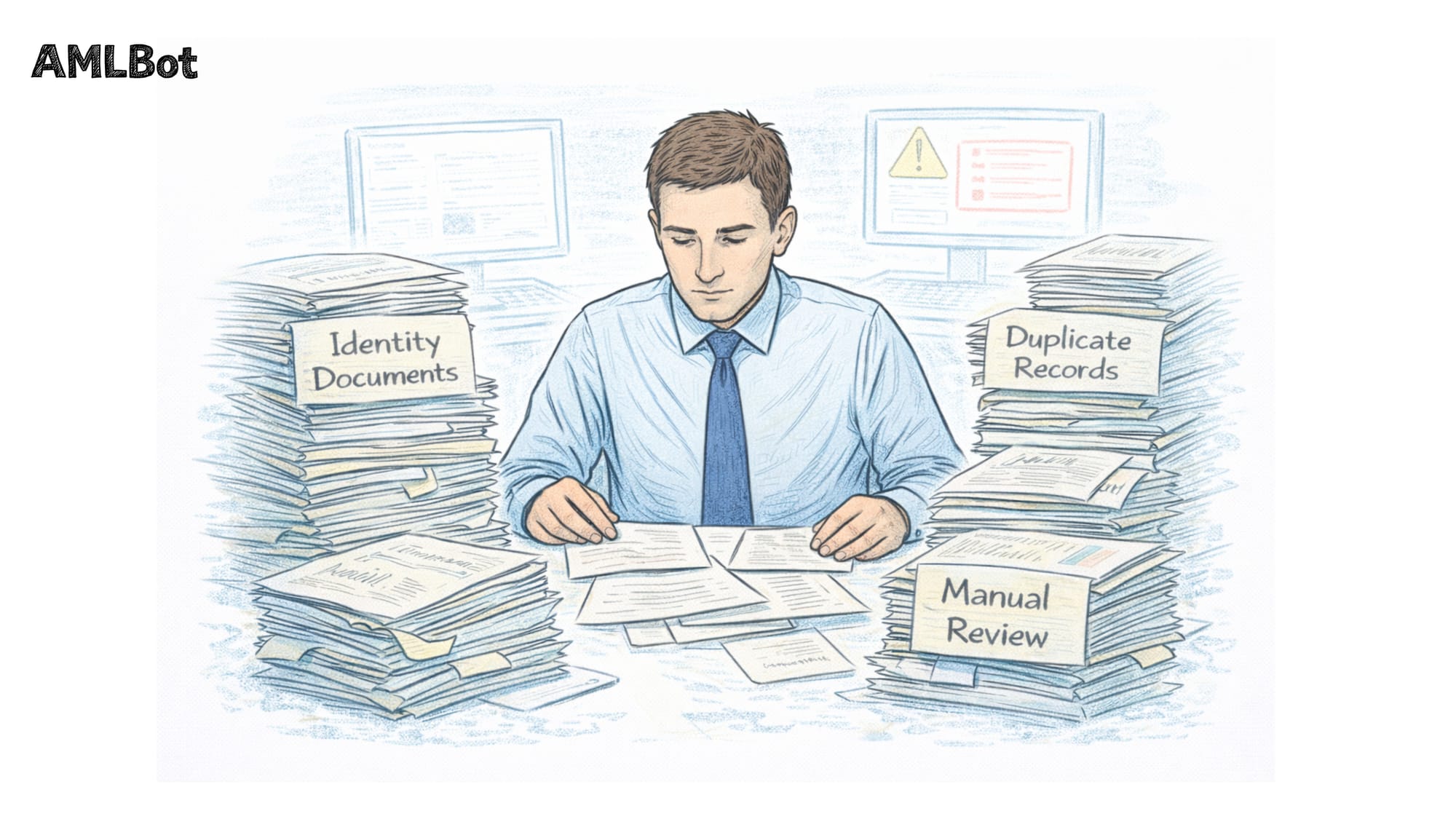

Manual and Fragmented Processes

CDD processes that are overly manual or fragmented across systems present another big challenge. In some firms, different aspects of due diligence are handled by different teams or systems that don’t talk to each other – for example, one system for initial KYC, another for screening, and spreadsheets for ongoing reviews. This fragmentation can lead to errors, duplicative work, or things falling through the cracks. A manual CDD process (e.g., analysts checking documents by eye, re-keying data, shuffling papers for approval) is not only slow and costly, but also prone to human error. Important details might be missed or not recorded properly.

When volumes are high – consider a fintech onboarding thousands of users per day – manual processes simply can’t keep up, resulting in backlogs or superficial checks. This was less of an issue decades ago when banking was slower-paced and branch-based, but in today’s digital environment, a manual approach can be a serious liability. It also hinders ongoing monitoring if data isn’t centralized. Compliance teams might not have a single customer view that includes KYC info, account activity, and risk scoring in one place.

Regulators have pointed out that inefficient CDD processes can themselves be a risk, because they sap resources and often lead to compliance gaps. For example, if analysts are spending time re-collecting documents that were already provided, they have less time to analyze unusual transactions. Fragmentation can also mean inconsistent application of policies – one branch or department might interpret CDD requirements differently from another.

The solution trends have been towards automation and integration: using centralized KYC utilities, workflow software that links all steps, and digital platforms where information is entered once and flows through the process. Many firms are also adopting client lifecycle management tools that provide end-to-end tracking of CDD and KYC tasks. While the user prompt specifically said not to delve into solutions, it’s worth noting that addressing manual and fragmented processes is crucial to strengthening CDD compliance. Those that don’t modernize may find themselves overwhelmed and at risk of non-compliance.

Conclusion

Why Strong CDD Is The Foundation Of AML And KYC Compliance

In conclusion, Customer Due Diligence is the foundation upon which effective AML and KYC compliance is built. A strong CDD program enables financial institutions and other businesses to truly “know their customers” – not just at a surface level, but in terms of risk and behavior. By diligently identifying and verifying customers, understanding beneficial ownership, assessing risk, and monitoring activity, institutions create a formidable barrier against illicit finance. Every other aspect of an AML program relies on the baseline established by CDD. If you don’t have accurate information on who your customer is and what risk they pose, you cannot reliably spot suspicious transactions or fulfill regulatory obligations.

We’ve seen that CDD is both a regulatory requirement and a prudent business practice. It protects the institution from legal penalties and reputational damage by ensuring compliance with AML regulations. It also helps safeguard the financial system more broadly by preventing criminals from abusing legitimate services. In the long run, investing in thorough CDD means fewer surprises – fewer cases where the organization unwittingly facilitates fraud or is caught off-guard by a scandal involving a client.

Moreover, a risk-based CDD approach allows businesses to be both compliant and efficient – focusing resources where the risks are highest (through Enhanced Due Diligence) and not overburdening low-risk relationships (with Simplified Due Diligence where appropriate). This proportional approach, endorsed by regulators worldwide, ensures that compliance efforts are meaningful and not just a checkbox exercise.

Finally, as industries evolve (with fintech innovations, crypto assets, etc.), the principles of CDD remain universally applicable and crucial. New technologies and sectors will adapt, but they too must implement the core steps of customer due diligence to maintain trust and integrity. In essence, strong CDD is the bedrock – it gives teeth to the phrase “Know Your Customer” and underpins the entire edifice of AML/CFT compliance.

-AMLBot Team

Follow AMLBot:

🔗 Website

🔗 Telegram

🔗 Support Team

🔗 LinkedIn

What is Customer Due Diligence (CDD) in AML Compliance?

Customer Due Diligence (CDD) is a core AML process used to identify customers, verify their identities, assess their risk levels, and monitor their transactions over time. The aim is to ensure the institution knows who it is doing business with and can detect potential money laundering or terrorist financing. CDD typically involves collecting customer information (and beneficial owner information for companies), verifying documents, assigning a risk rating, and conducting ongoing monitoring to prevent the misuse of the financial system.

How does Customer Due Diligence differ from KYC?

KYC (Know Your Customer) primarily refers to the identity verification part of onboarding – confirming a customer’s identity with reliable documents and checks. CDD (Customer Due Diligence) is broader: it includes KYC and additional steps like risk assessment, checking the customer’s background and purpose of the relationship, identifying beneficial owners, and ongoing monitoring. In short, KYC is one component of CDD. KYC ensures you know who the customer is; CDD ensures you understand the customer’s risk and behaviors on an ongoing basis.

Why is Customer Due Diligence required under AML Regulations?

Regulators require CDD because it is fundamental to preventing illicit financial activity. By performing CDD, financial institutions can identify and mitigate risks posed by their customers. Without CDD, criminals could more easily use anonymous accounts or complex structures to launder money or finance terrorism. Thus, AML laws mandate CDD to help institutions “Know their Customers” and detect suspicious activity, thereby protecting the integrity of the financial system. In many jurisdictions, CDD is explicitly written into law as an obligation for banks, fintechs, and other covered businesses.

What are the Main Components of the Customer Due Diligence Process?

Key components of CDD include: (1) Customer Identification – collecting the customer’s identifying information; (2) Customer Verification – verifying that information (e.g., confirming IDs are valid); (3) Beneficial Ownership Identification – determining who the ultimate owners/controllers are if the customer is a legal entity; (4) Risk Assessment and Profiling – evaluating the customer’s risk level (low/medium/high) using a risk-based approach; and (5) Ongoing Monitoring – continuously monitoring transactions and periodically updating customer information.

What is the Difference Between CDD and Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD)?

Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD) is essentially an augmented form of CDD applied when a customer is deemed high-risk. Under standard CDD, all customers undergo basic identification, verification, and risk assessment. If that assessment flags a customer as higher risk (due to factors like large transactions, high-risk country, complex ownership, etc.), EDD comes into play. EDD involves more in-depth checks – for example, gathering extra information about the customer’s source of funds, performing more frequent reviews, senior management sign-off, and closer scrutiny of transactions. So, while CDD is for everyone, EDD is a deeper dive reserved for high-risk customers or situations.

When is Simplified Due Diligence (SDD) Allowed?

Simplified Due Diligence (SDD) may be allowed when a customer is assessed to pose a low risk of money laundering or terrorist financing, and when local regulations permit a simplified approach. Examples include customers like government entities or listed companies, or low-value accounts/products with restrictions. In such low-risk cases, regulators might allow reduced identification or verification requirements. However, SDD is only allowed in clearly defined situations, and never when there is any suspicion of wrongdoing or when higher-risk factors exist. Essentially, SDD is the bare minimum CDD applied to low-risk scenarios, subject to regulatory guidelines.

What is Beneficial Ownership in the Context of CDD?

In CDD, beneficial ownership refers to identifying the natural person(s) who ultimately own or control a customer that is not an individual. For example, if your customer is a corporation or trust, there are people behind it who benefit from its activities (shareholders, trust settlors/beneficiaries, etc.). CDD requires that you determine who those ultimate owners/controllers are – the beneficial owners – typically anyone with a significant percentage ownership or controlling interest. Identifying beneficial owners is crucial because it prevents bad actors from hiding behind legal entities. Beneficial ownership transparency ensures you know “who’s really behind the account” as part of due diligence.

How does a Risk-Based Approach affect Customer Due Diligence?

A risk-based approach tailors the CDD efforts to the level of risk each customer presents. This means that instead of applying identical procedures to everyone, an institution will do more for higher-risk customers and less for lower-risk customers. For instance, if a customer is low-risk, the institution might gather just the essential information (SDD), whereas a high-risk customer will undergo extensive EDD (additional documents, more frequent checks). The risk-based approach is endorsed by regulators because it makes compliance more effective and efficient – resources are allocated in proportion to risk. In practice, it affects CDD by determining how much information to collect, how rigorously to verify, and how often to update or monitor for each customer based on their risk profile.

Are Customer Due Diligence Requirements the Same Across all Industries?

The core principles of CDD are consistent across industries – any business subject to AML laws must identify customers, verify identities, understand risk, and monitor for suspicious activity. However, the implementation can vary. For example, banks have very detailed CDD procedures given their high-risk exposure and regulatory oversight. Fintech and payment providers apply the same rules but often through digital means and with a tech-driven process. Crypto exchanges also follow CDD principles but must adapt them to the crypto context (linking digital wallet addresses to customer identity, for instance). So while the requirements (ID, verification, risk-based approach, etc.) are fundamentally the same, the way they are carried out may differ to suit the business model and regulatory specifics of each industry.

Why is Ongoing Monitoring an Important Part of Customer Due Diligence?

Ongoing monitoring is crucial because a customer’s risk profile and activities can change over time. Initial CDD gives a snapshot at onboarding, but without monitoring, you’d miss subsequent red flags. Ongoing monitoring involves watching transactions for anomalies (which could indicate money laundering) and keeping customer information up to date. This way, the institution can detect suspicious patterns (e.g., an account suddenly receiving large international wires inconsistent with the customer’s profile) and take action, such as investigating or filing a report. It also ensures compliance over the long term – regulators expect institutions to not only vet customers at the start but also to remain vigilant throughout the customer relationship. In essence, ongoing monitoring makes CDD a continuous effort rather than a one-time checkbox, thereby strengthening the overall AML defense.